single words

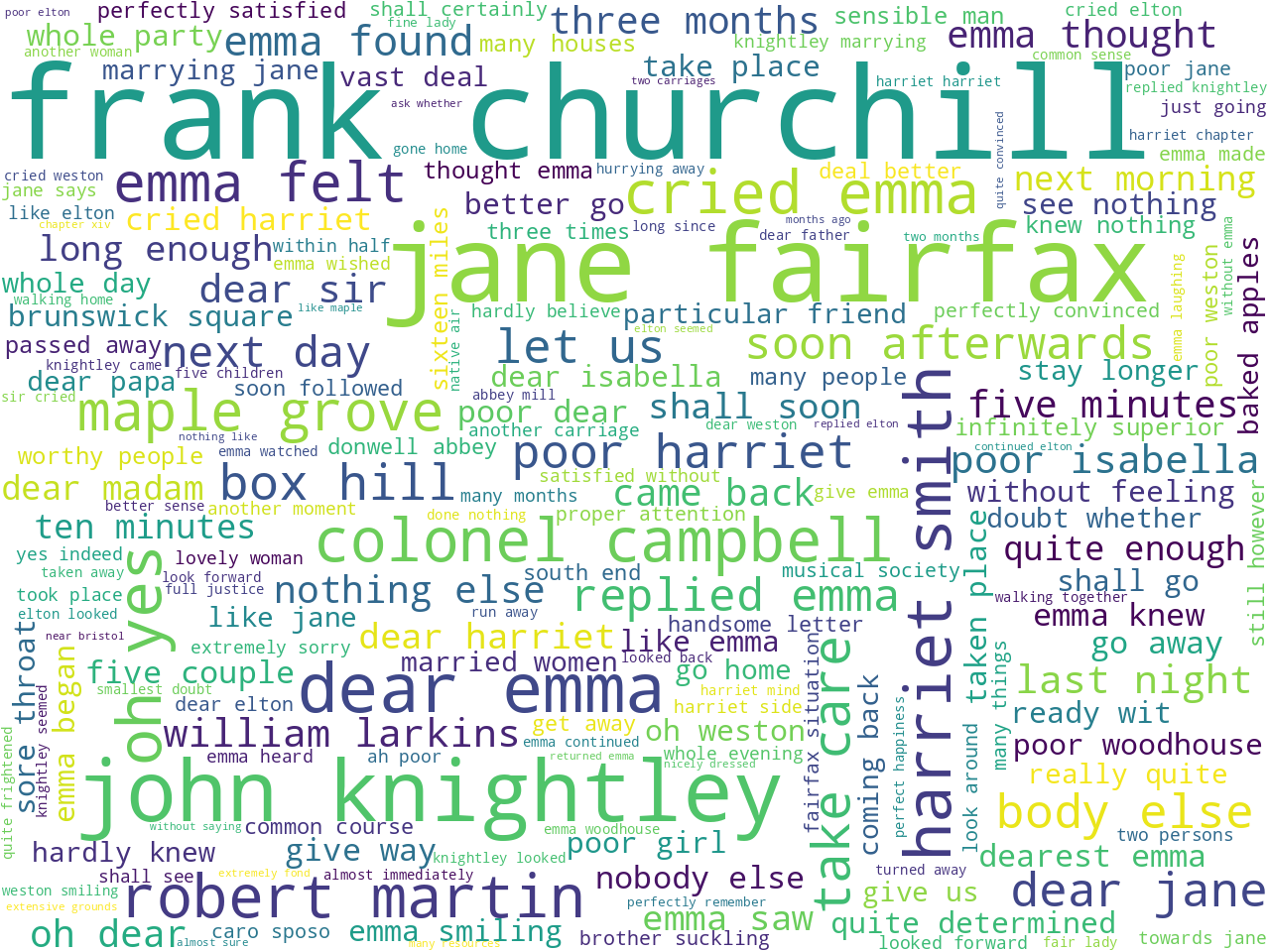

bigrams

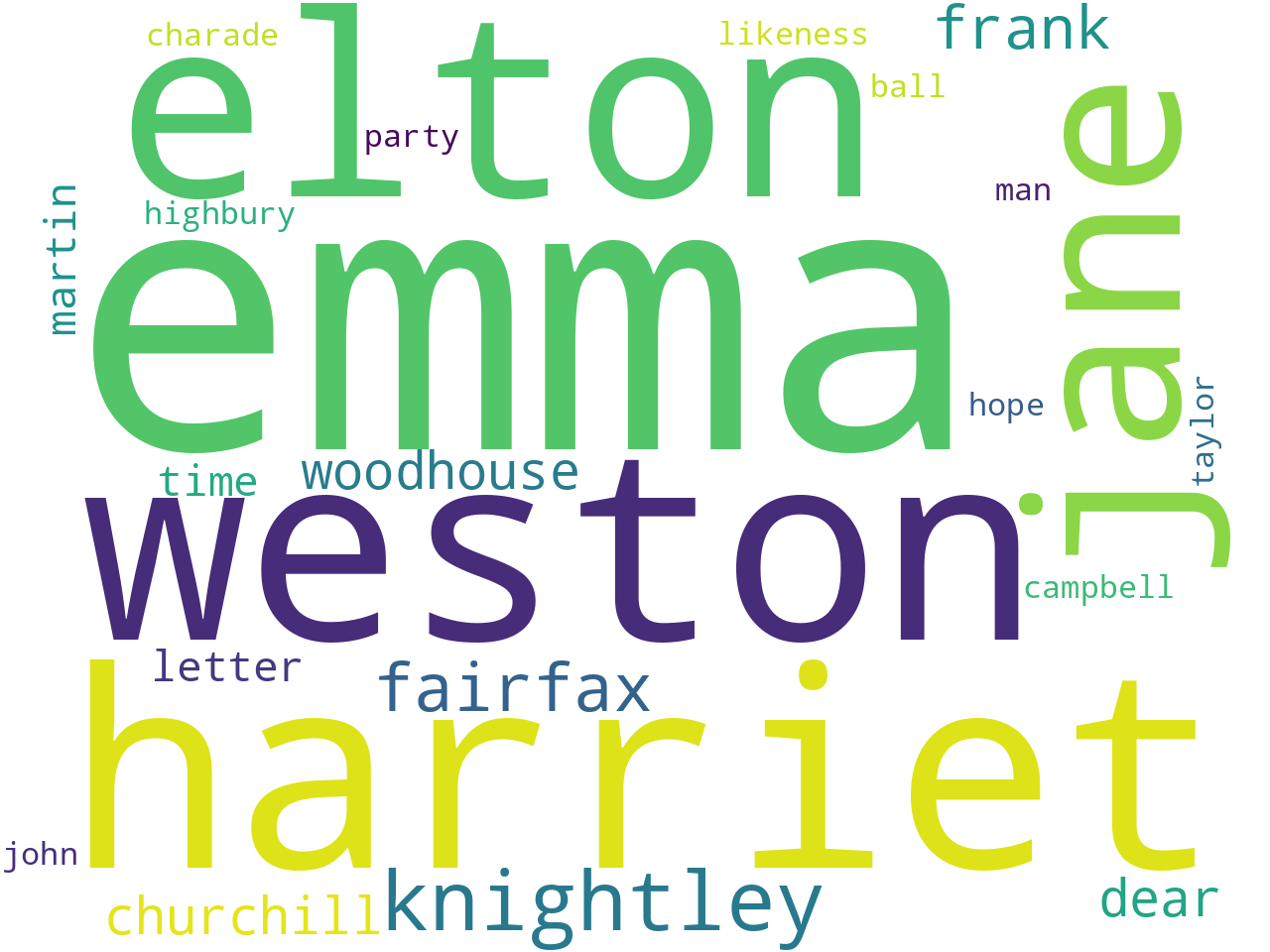

keywords

It's all about Emma,… and the people around her.

Emma -- published in 1815 -- is one of the handful of novels written by the Victorian author Jane Austen. Put very succinctly, it is the story of Emma and the people around her.

My summary (above) and "distant reading" (below) has been done against a version of Emma found at Project Gutenberg, and a copy has been cached locally, just in case.

As far as novels go, Emma is not very long -- only 160,000 words. By comparison, the Bible is about 800,000 words long, and Melville's Moby Dick is about 218,000 words long. Nor is the book very difficult to read; Emma has a Flesch readability score of 73, where 0 means nobody can read it, and 100 means anybody can read it. Based on my experience, scores in the 70's are typical for popular novels.

I used a large-language model to summarize each of the fifty-five chapters in Emma, and from the results, I see a lot of Emma and the names of people. All of the summaries are available here, and a few of the more interesting ones are included below:

Emma Woodhouse has lived for 21 years in a comfortable home and happy disposition. Her mother died long ago and she had a governess, Miss Taylor, who died recently. Emma and Miss Taylor had been friends for 16 years. Miss Taylor married Mr. Weston. Emma mourned the loss of her friend.

Emma has given Harriet's fancy a proper direction and raised the gratitude of her young vanity to a very good purpose. Emma is convinced that Mr. Elton's falling in love with Harriet. He talked of Harriet warmly and praised her. Emma wants Harriet's picture.

Emma is worried about Frank Churchill. He came to Highbury for a couple of hours. They met with the utmost friendliness. He was in high spirits, but he was not without agitation. Emma suspects he is less in love than he had been.

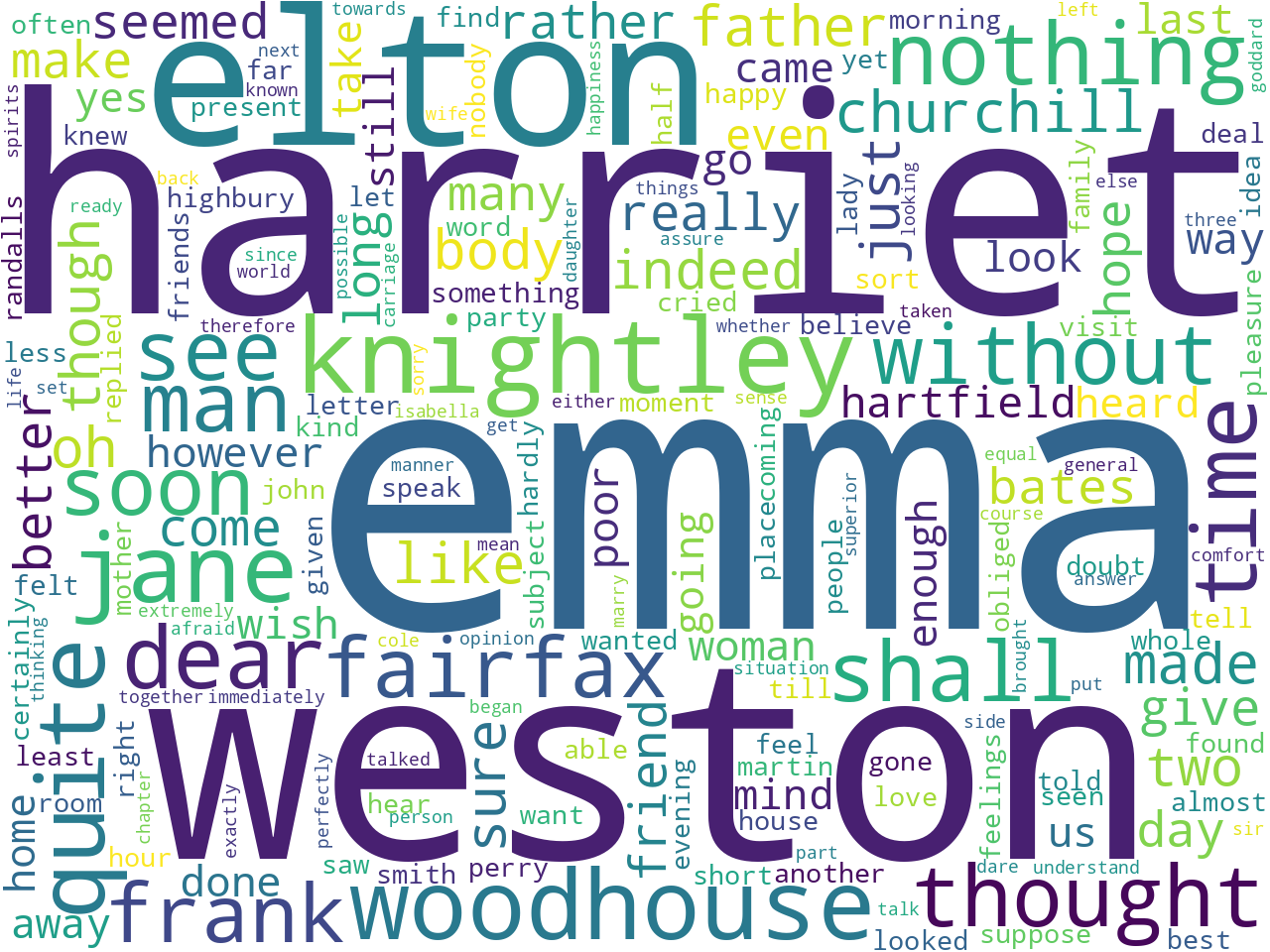

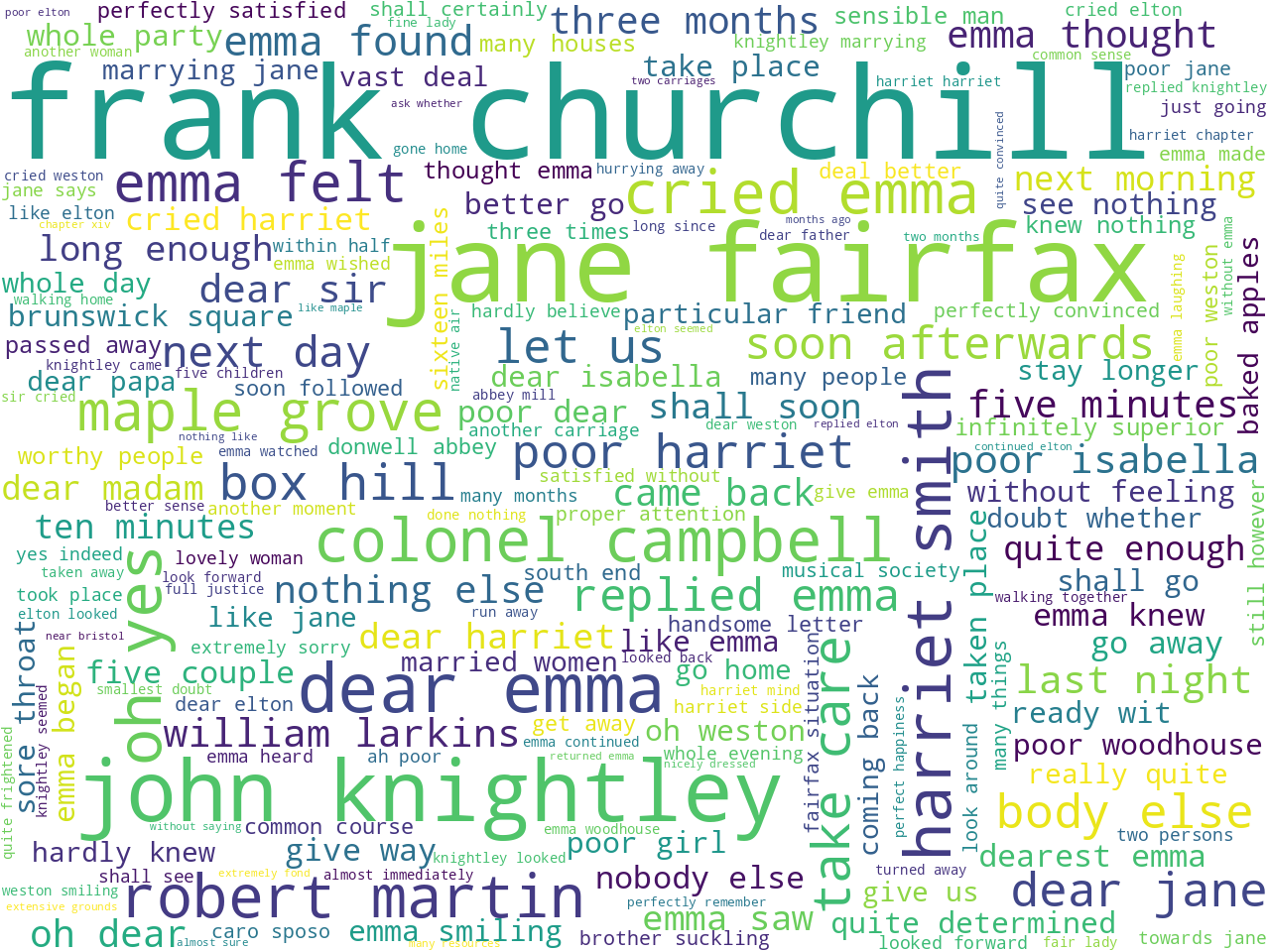

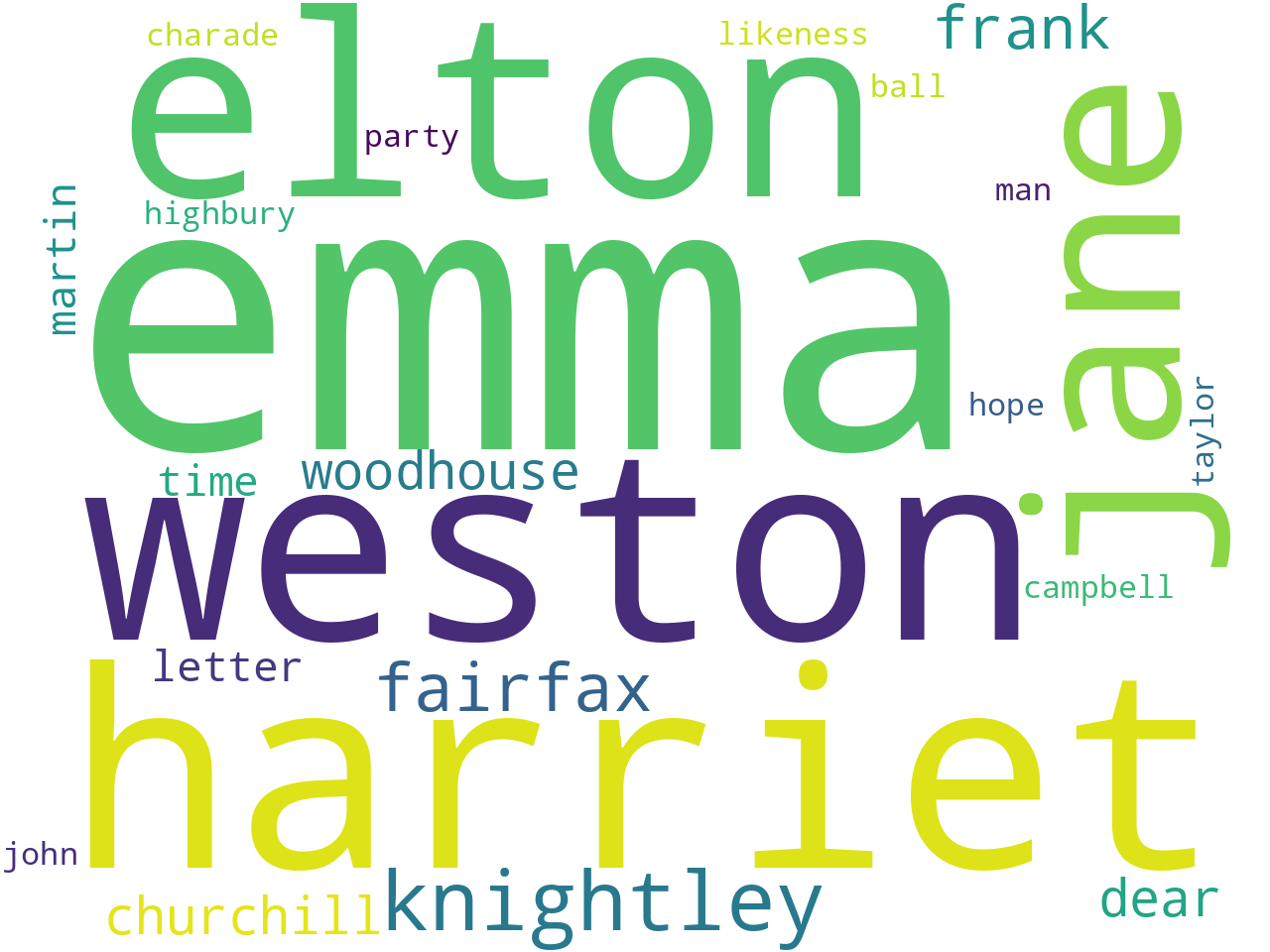

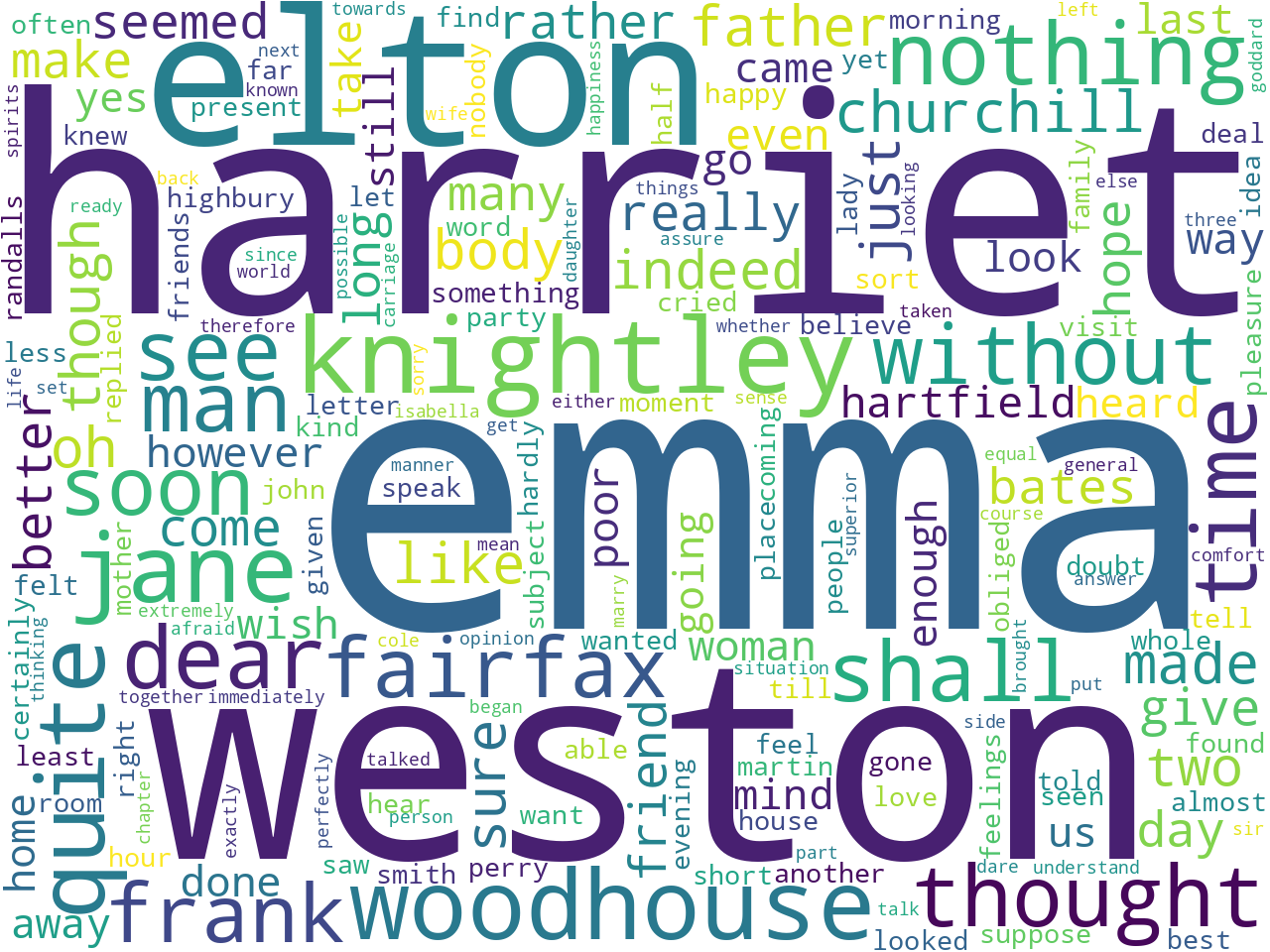

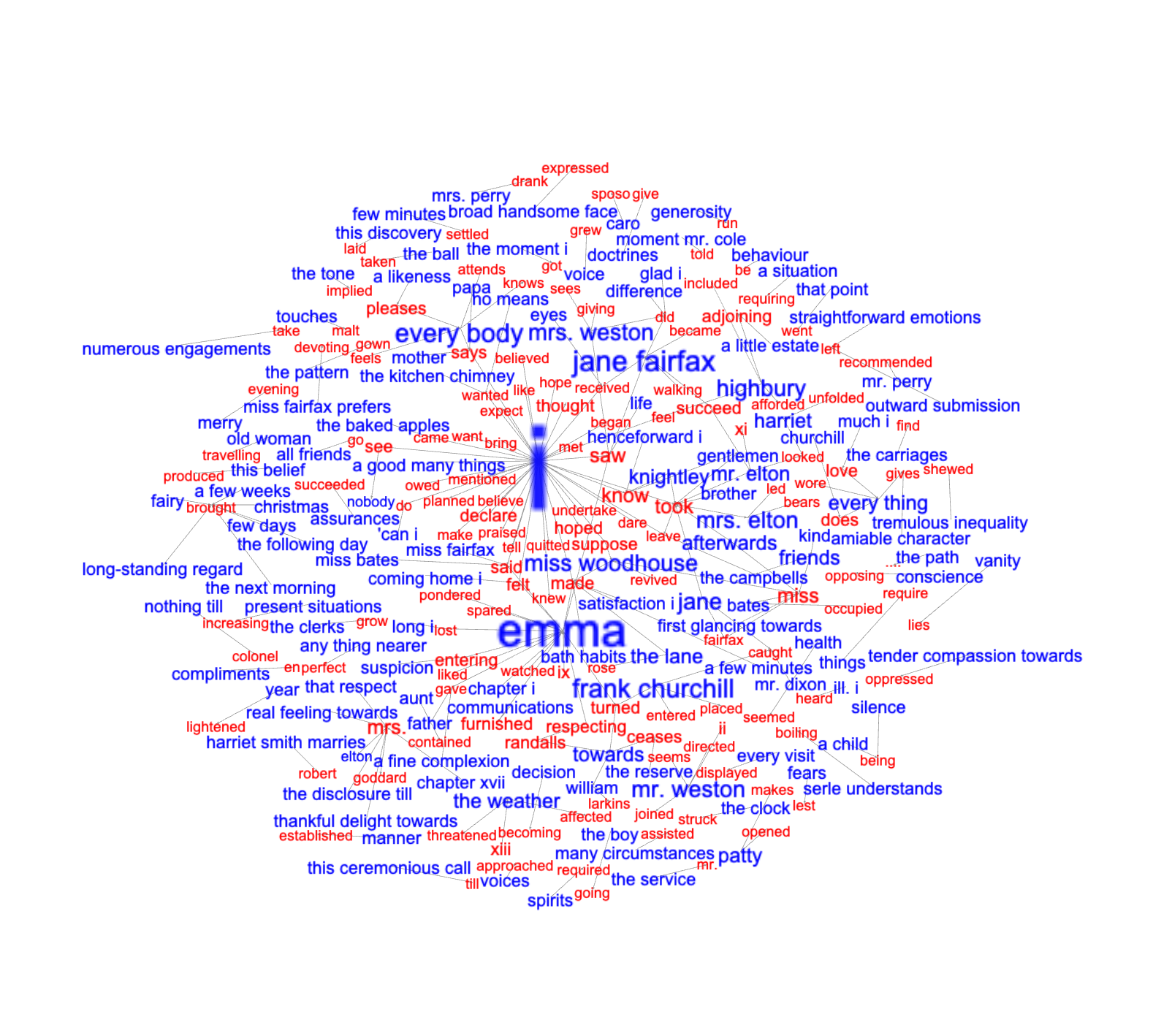

Rudimentary frequencies of word, phrases, and keywords begin to allude to the aboutness of any corpus, and Emma is no different. The following word clouds illustrate the frequency of single words, two-word phrases ("bigrams"), and computed keywords (kinda like "subject headings"). Notice how the names of people dominate:

single words |

bigrams |

keywords |

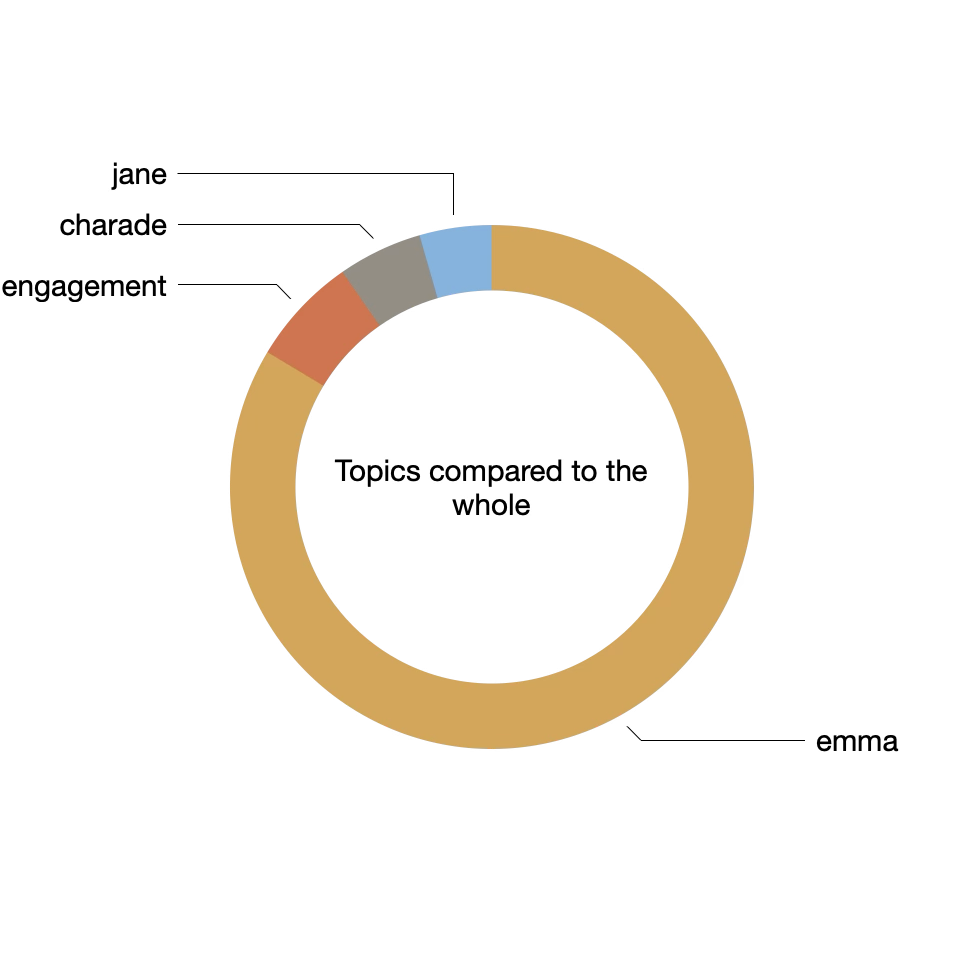

Topic modeling is a computing process used -- among other things -- to enumerate latent themes in a corpus. It is a form of machine learning called "clustering". Like just about any other modeling process done by computers, there are many ways to topic model; topic modeling is not necessarily deterministic. That said, when I topic model Emma four themes present themselves, below, and when I topic model for a number greater than four, then the overall result does not change very much. The theme of "emma" always dominates. The visualizations echo the dominance of the theme "emma":

| labels | weights | features |

|---|---|---|

| emma | 3.0353 | emma harriet weston knightley elton time great woodhouse quite nothing dear always |

| engagement | 0.2443 | engagement affection attachment snow circumstances happiness behaviour letter feeling heart resolution reflection |

| charade | 0.18906 | charade likeness sit eye sea lines alone wingfield maid picture smith's south |

| jane | 0.16189 | jane fairfax bates campbell dixon colonel cole dancing campbells instrument dance crown |

topics |

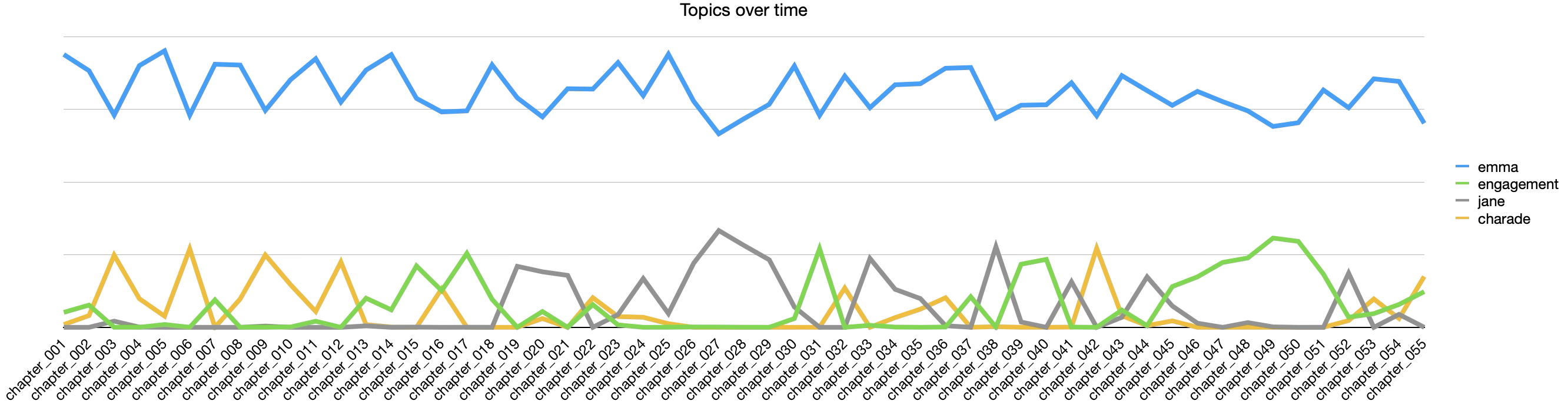

topics over time |

In the line chart, notice how the themes ebb and flow over the course of the book. It might be interesting to investigate this more carefully. There seems to be some sort of back and forth going on.

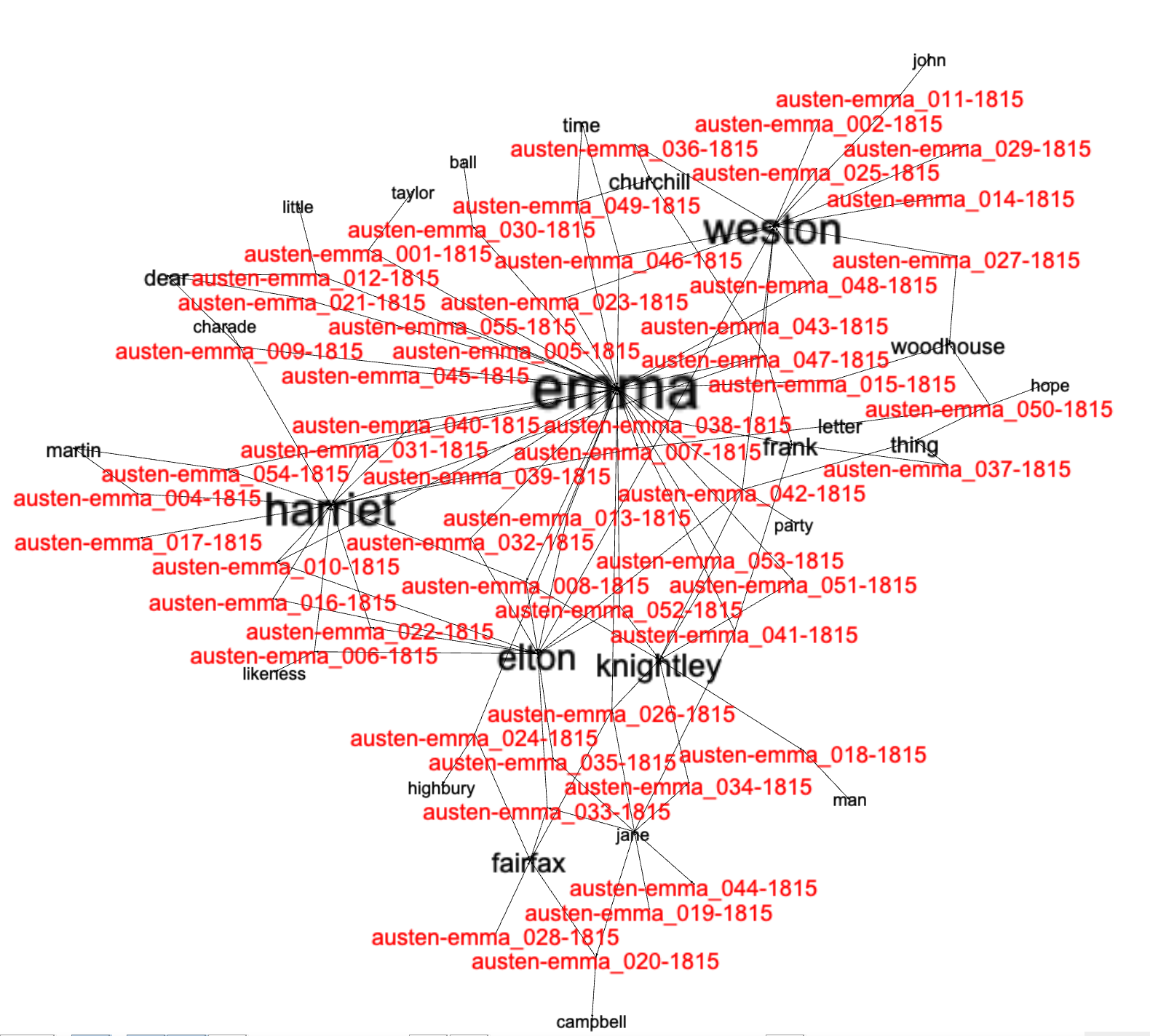

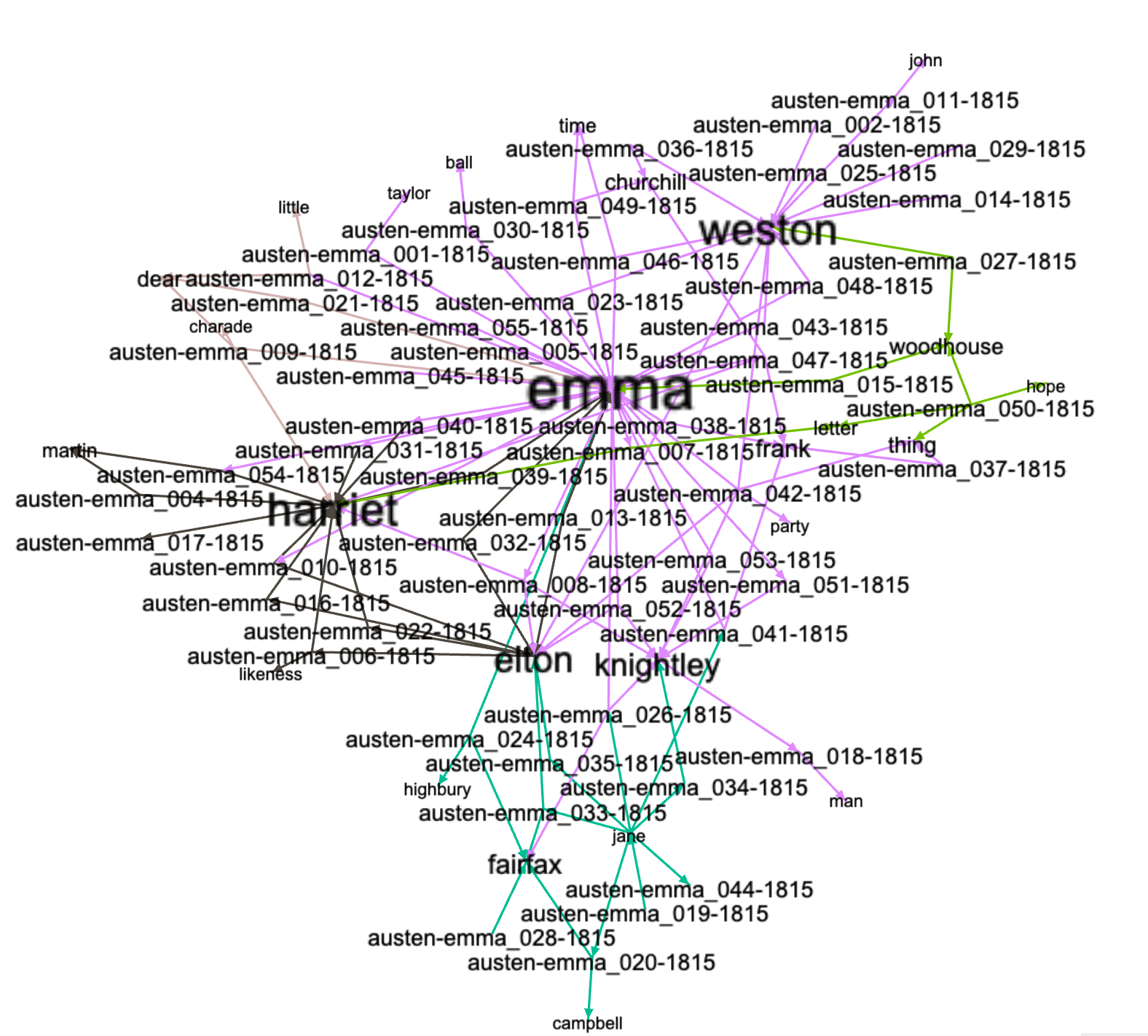

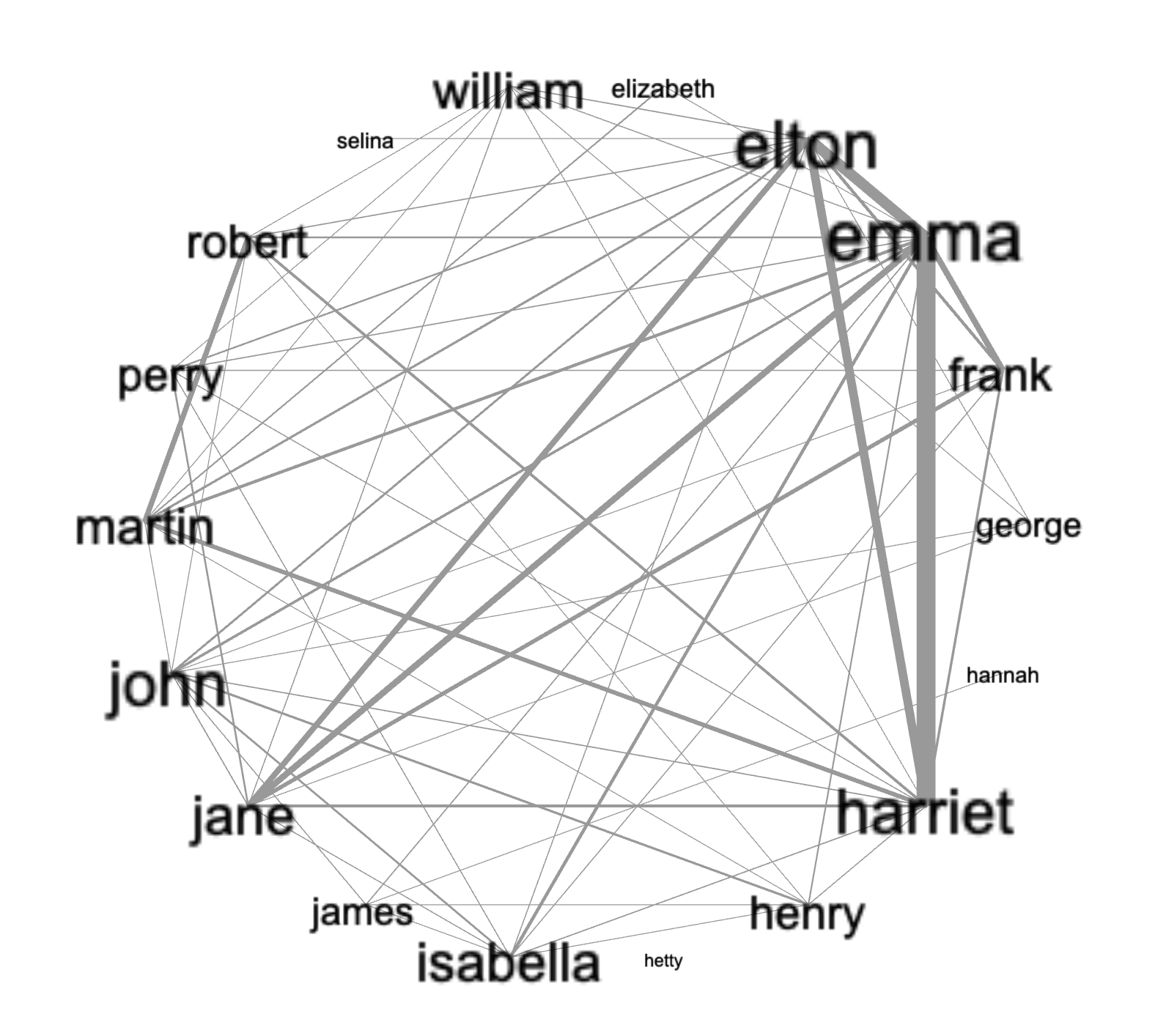

Analyzing (reading) Emma through the lens of network graphs echos the same things. In the first graph items and keywords are hi-lighted. Notice how the keyword "emma" is the largest and most central feature. When a clustering method ("modularity") is applied to the network graph, only a small handful of "neighborhoods" present themselves -- one around "emma", and the other around "jane". (By the way Jane's last name is Fairfax.) Such is illustrated in the second graph. This analysis does not output the types of interactions Emma has with the people around her, but it can allude to the people Emma has interactions with and to what degree. More specifically, if I assume sentences containing pairs of names of people connote some sort of relationship between the people, then I can count such sentences, create an edges table, and graph the result. Such is what I did, and based on this, I assert Emma has the greatest number of interactions with Harriet, Jane, and Elton:

items and keywords |

clusters |

interactions |

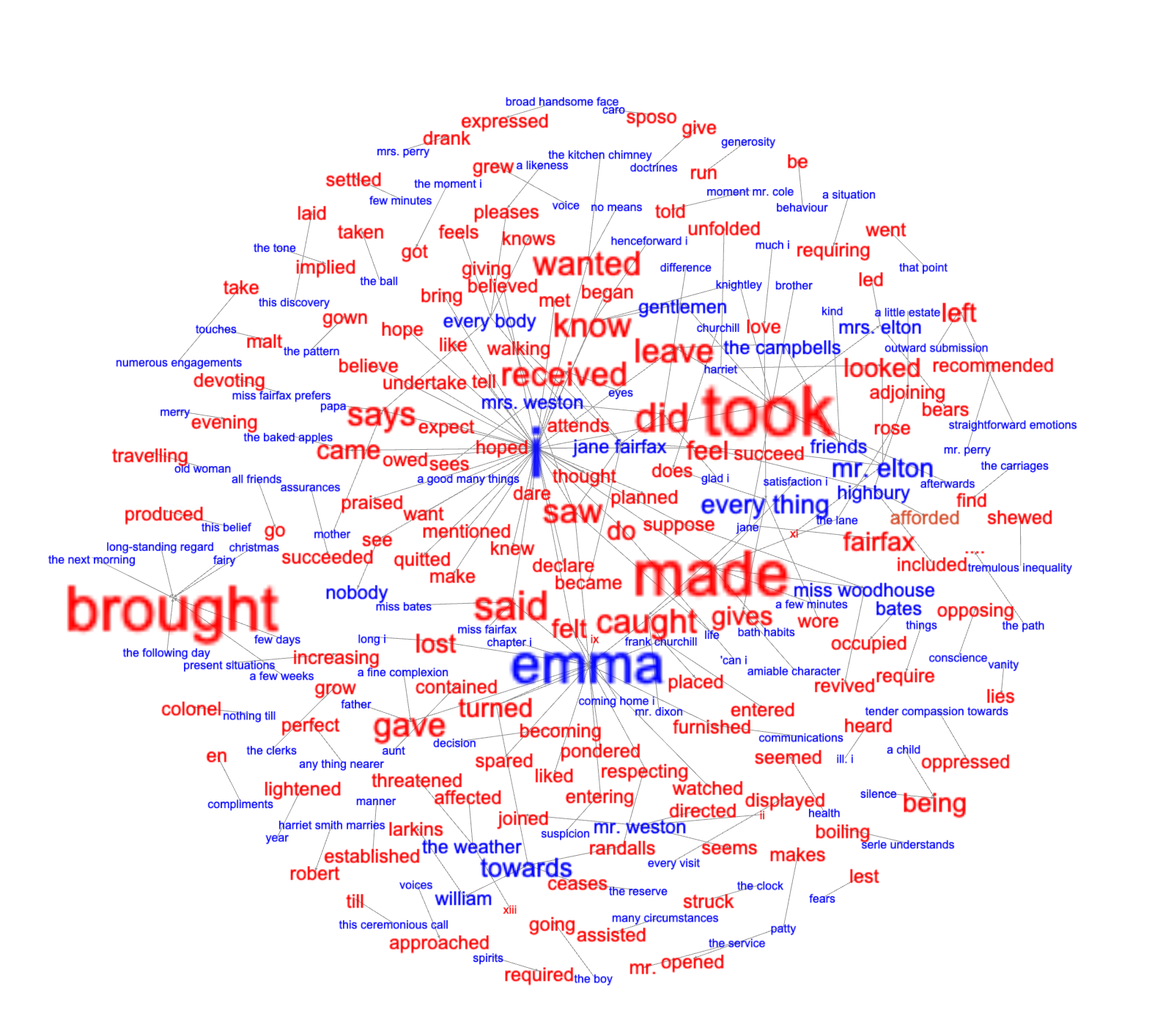

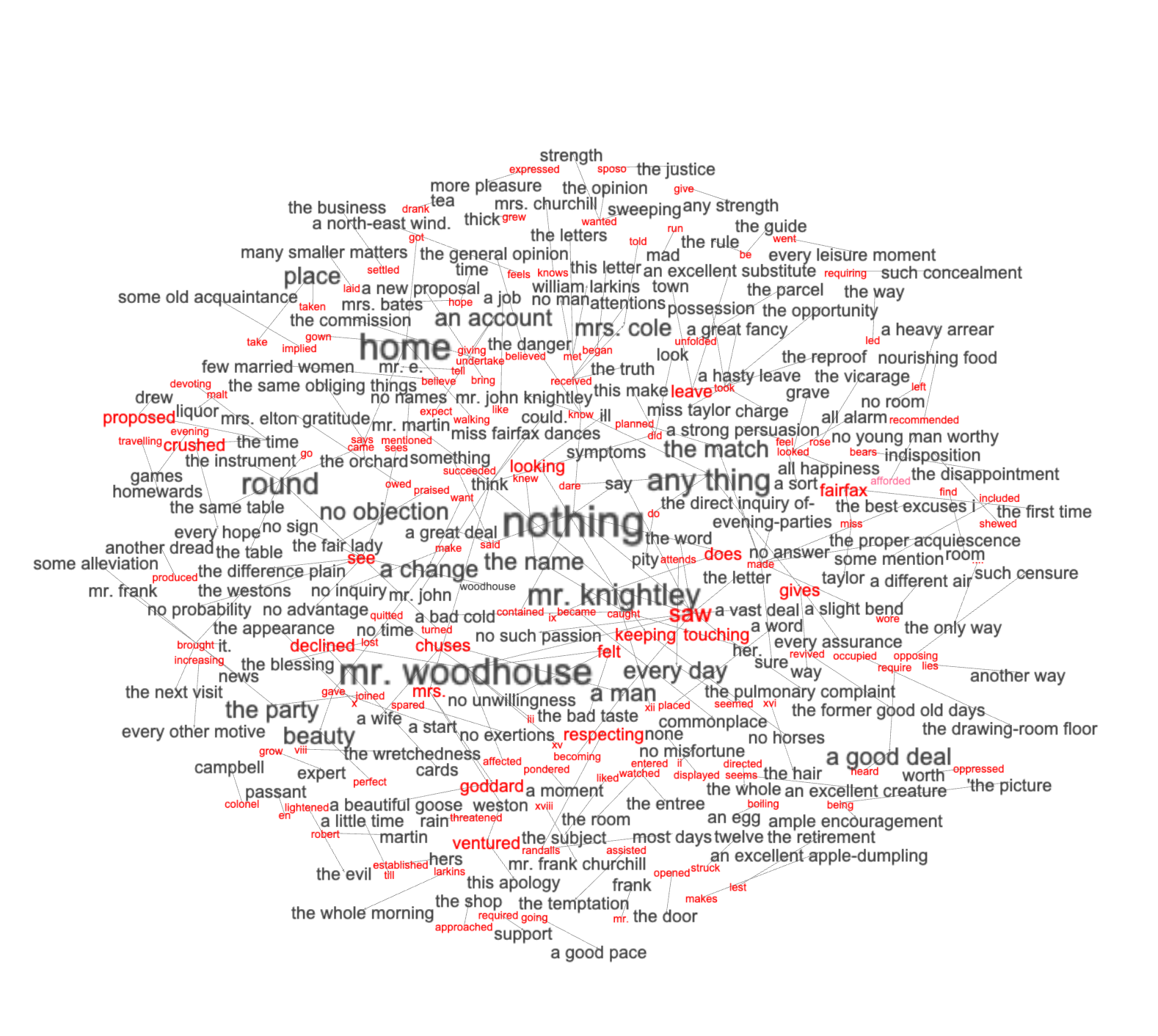

Understanding what nouns exist in a corpus helps one understand what things exist in a corpus. Understanding what verbs exist in the same corpus helps one understand what those things do. In an effort to understand what nouns are in Emma, what they do, and to what degree, I extracted all the sentence of the form subject-verb-object. I then visualized the result in the following three graphs. The first illustrates what subjects dominate. Notice how the subjects are people. The second graph illustrates what those subjects do, and words like "took", "brought", and "said" stand out. The final graph illustrates what the actions were done against. While it is not obvious, the items in the third graph leans towards very generic things (like "nothing" or "anything") and people, essentially male people (like "mr. woodhouse", "mr. knightly", or "a man"):

subjects |

verbs |

objects |

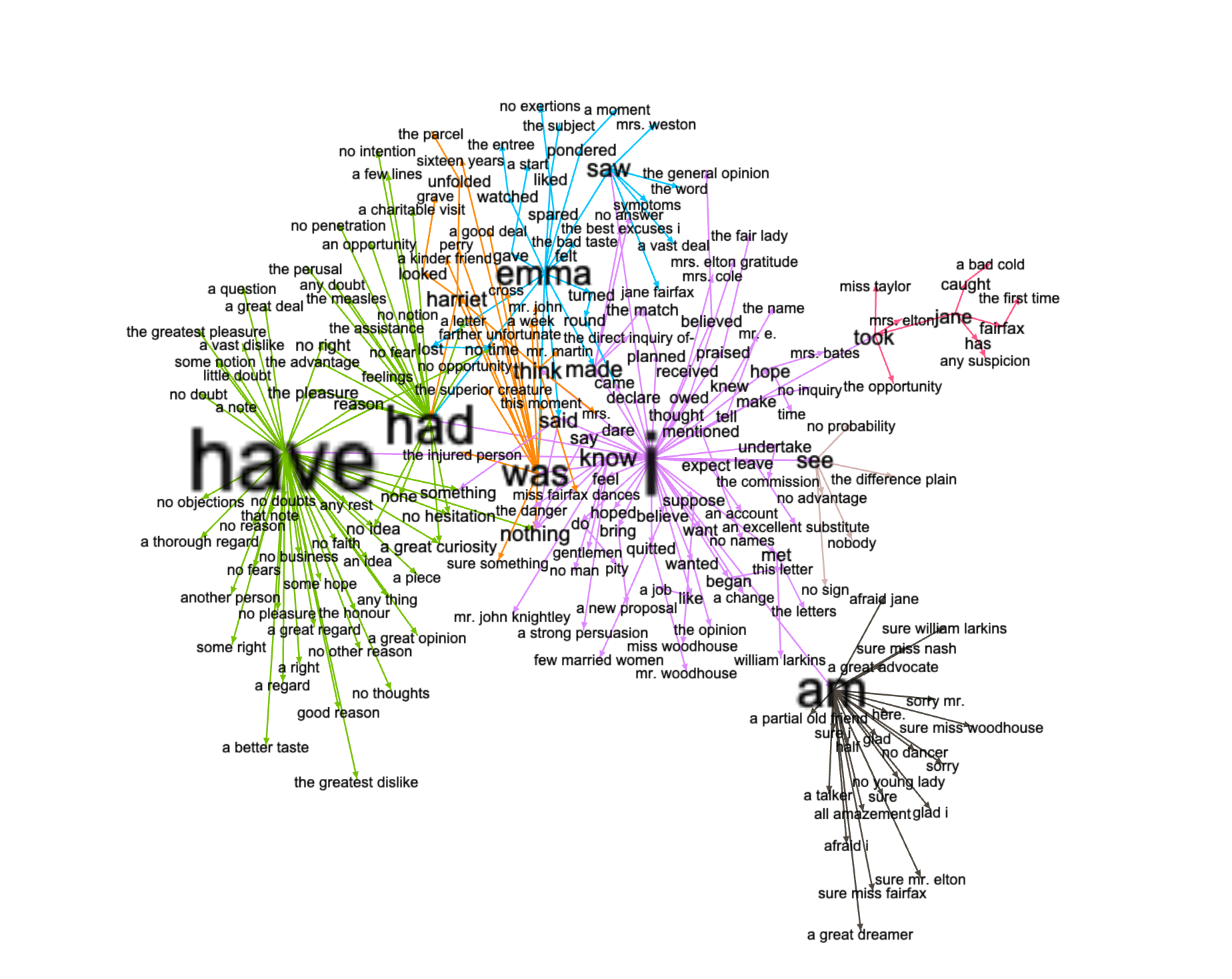

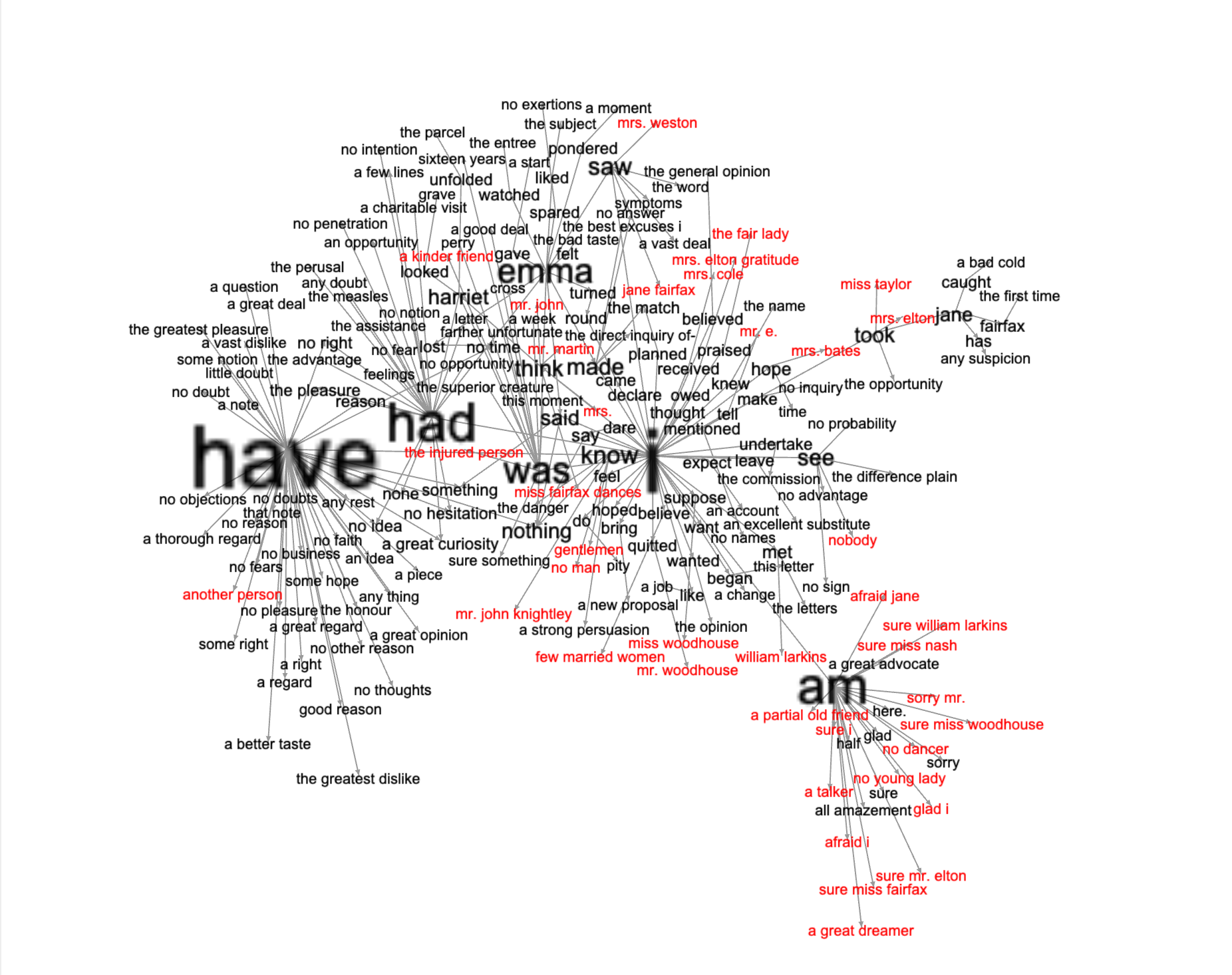

The following two visualizations riff on sentences with subject-ver-object forms. The first illustrates what the story's primary characters (plus pronouns) do and to what. Again, Emma stands out. In the second, I marked in red the objects of the sentences alluding to people. I was hoping to see a greater number of people in the objects of the sentences, but alas:

characters plus pronouns |

objects alluding to people |

As a liberal artist, I am personally interested in "big" ideas such as truth, beauty, love, honor, and justice. Moreover, I am always on the lookout for definitions of these ideas. But alas, concordancing for these sorts of words returns few results. The word "love" returns seemingly the greatest number of results, but I don't see very many allusions to what love is. Maybe such is a characteristic of non-expository writing; instead of being told things directly, maybe the reader is expected to infer? The phrase "in love" appears rather often, and people are in love with a person, usually a female. A concordance of the every occurrence of the word love is cached locally:

a very musical man, and in love with another woman--engaged to

Mr. Elton should really be in love with me,--me, of all

worse that Harriet should be in love with Mr. Knightley, than with

Harriet, that she could be in love with more than three men

Frank Churchill.--He had been in love with Emma, and jealous of

so many errors, have been in love with you ever since you

the great goodness of being in love with him; but though she

like the pretence of being in love with her, instead of Harriet;

the idea of not being in love with her, that I should

fully convinced of his being in love with Harriet. It was through

glad I have done being in love with him. I should not

cried Harriet, "of his being in love with her?--You, perhaps, might.--

his business. He is desperately in love and means to marry her." "

into consideration now." "Mr. Elton in love with me!--What an idea!" "

supposed; till they do fall in love with well-informed minds instead

had the misfortune to fall in love with her, or that he

done for me, except falling in love with her when she is

family, and Miss Churchill fell in love with him, nobody was surprized,

as deeply and as happily in love as myself.--Whatever strange things

But he had fancied her in love with him; that evidently must

but one thing--Who is in love with her? Who makes you

they say every body is in love once in their lives, and

clear thing he was less in love than he had been. Absence,

she must be a little in love with him, in spite of

might not be making me in love with him?--very wrong, very

quite embarrassed.--He was more in love with her than Emma had

always so much the most in love of the two, were to

her to be very much in love with a proper object. I

man undoubtedly, and very much in love with Harriet; but still, he

thing denotes it--very much in love indeed!--and when he comes

Mrs. Weston, and so much in love with Miss Fairfax, and she

reason to believe as much in love with her as ever,) to

falling in love, if not in love already. She had no scruple

a certain friend of ours in love with the lady." "True. But

than his passion. A poet in love must be encouraged in both

Elton should not be really in love with her, or so particularly

if not of being really in love with her, of being at

truth, prove herself more resolutely in love than Emma had foreseen; but

to the woman he was in love with, how to be able

Through a process called "distant reading", I have tried to characterize Jane Austen's book, Emma. Without a doubt, Emma is the main character of the story, and no matter how the text is observed, the other primary things in the story are people. I illustrated what those people do and to what other things. I expected (hoped) those other things would be people, but that was not necessarily what I observed. I wish my distant reading processes would be able to figure out story lines. The closest I can get is to compute summaries of each chapter and then apply traditional reading to the result. Want a synopsis? See the computed summaries. For extra credit, take a closer look at the topics over time line chart, and see if you can articulate how the story ebbs and flows.

http://carrels.distantreader.org/curated-emma_by_austen-gutenberg/index.zip

Eric Lease Morgan <eric_morgan@infomotions.com>

Lancaster, Pennsylvania (United States)

September 1, 2025