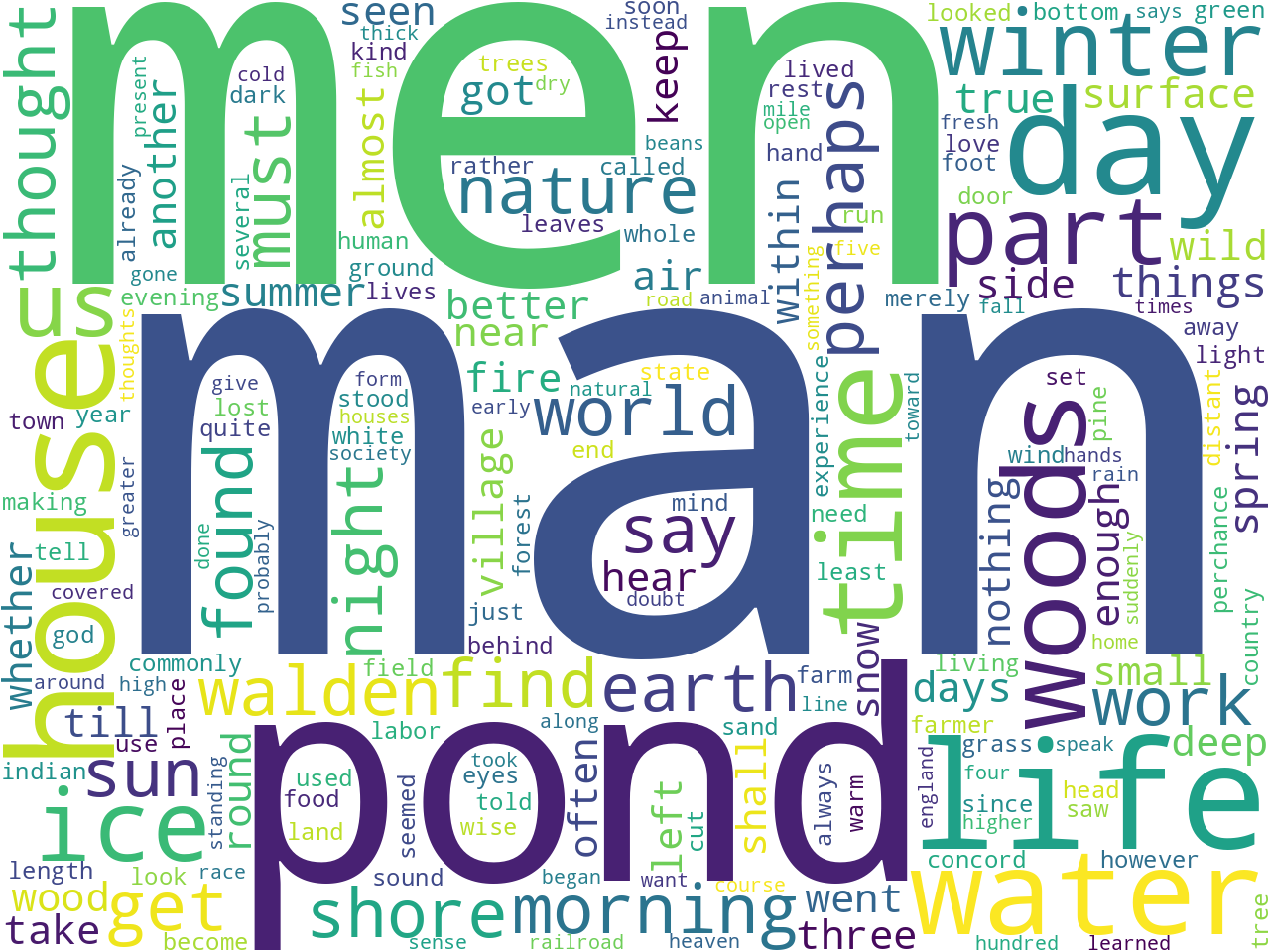

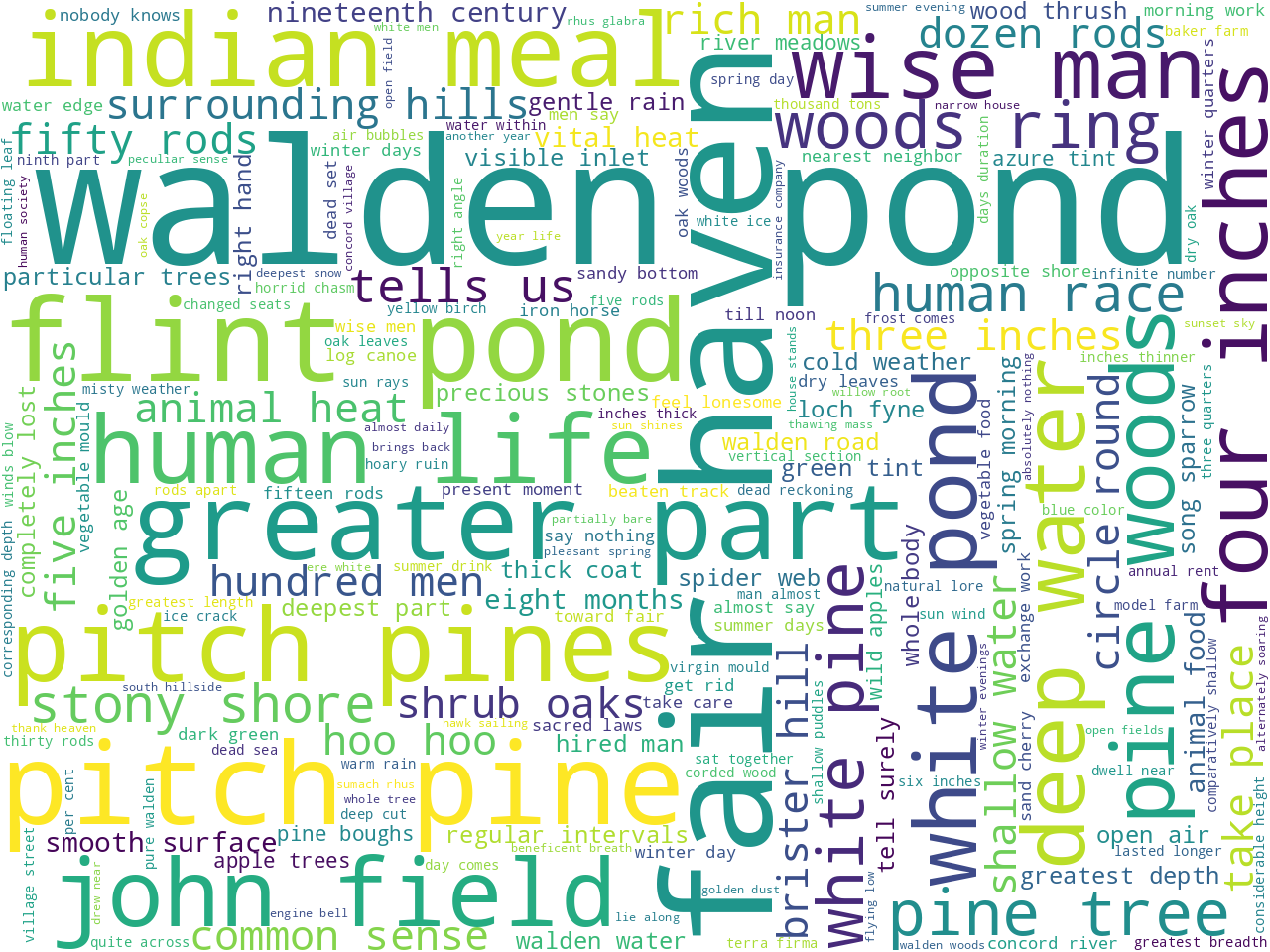

unigrams

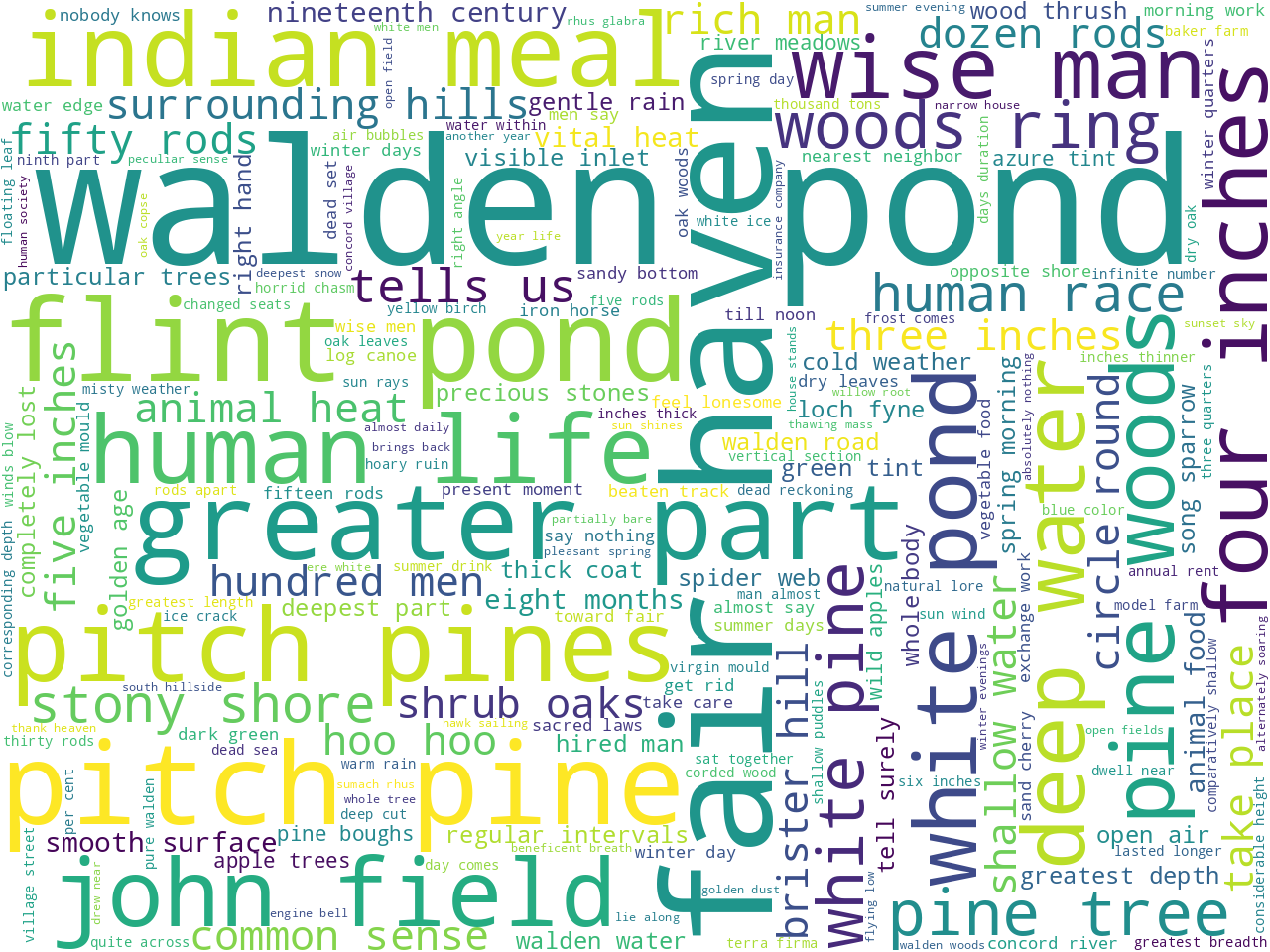

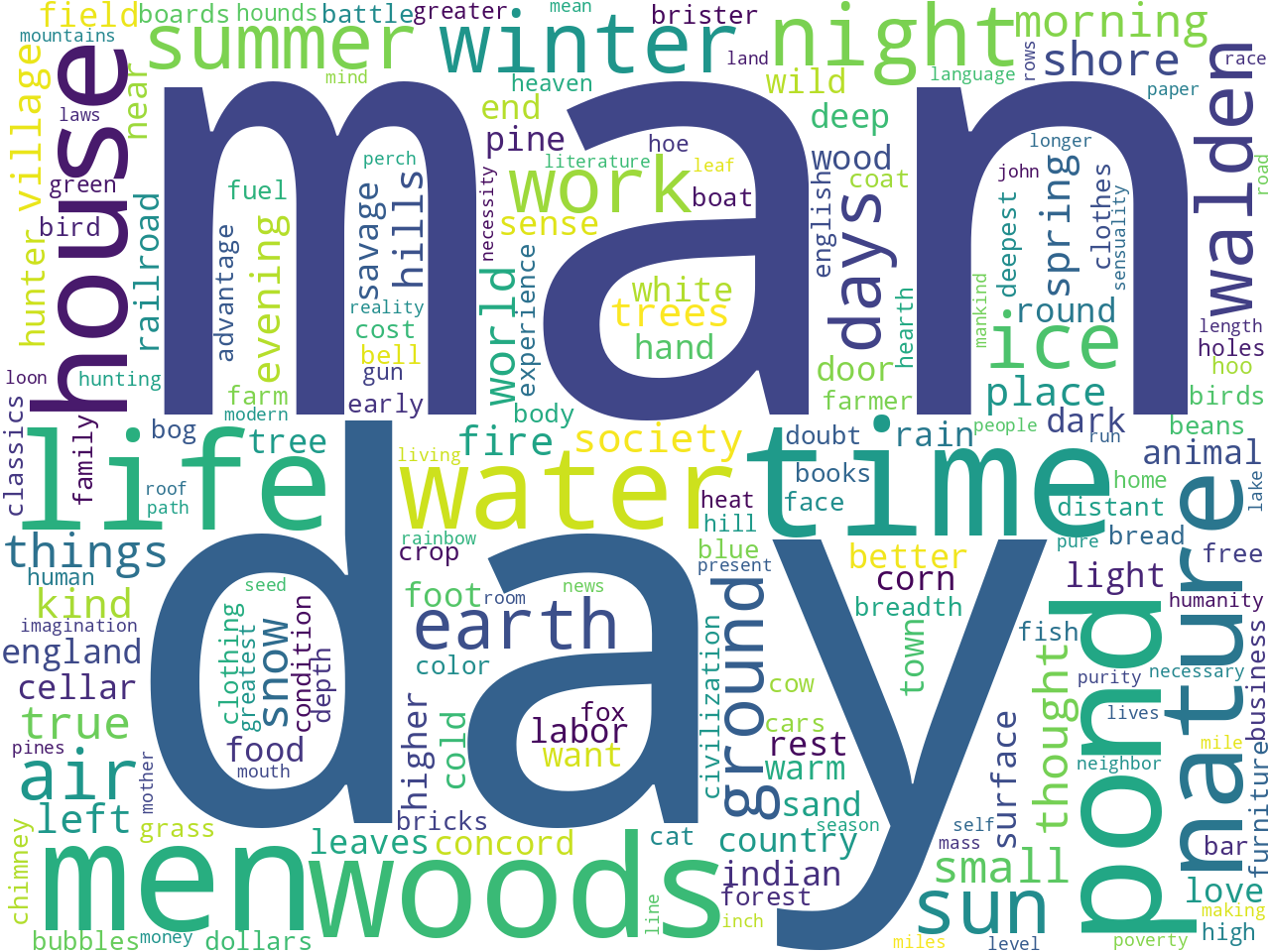

bigrams

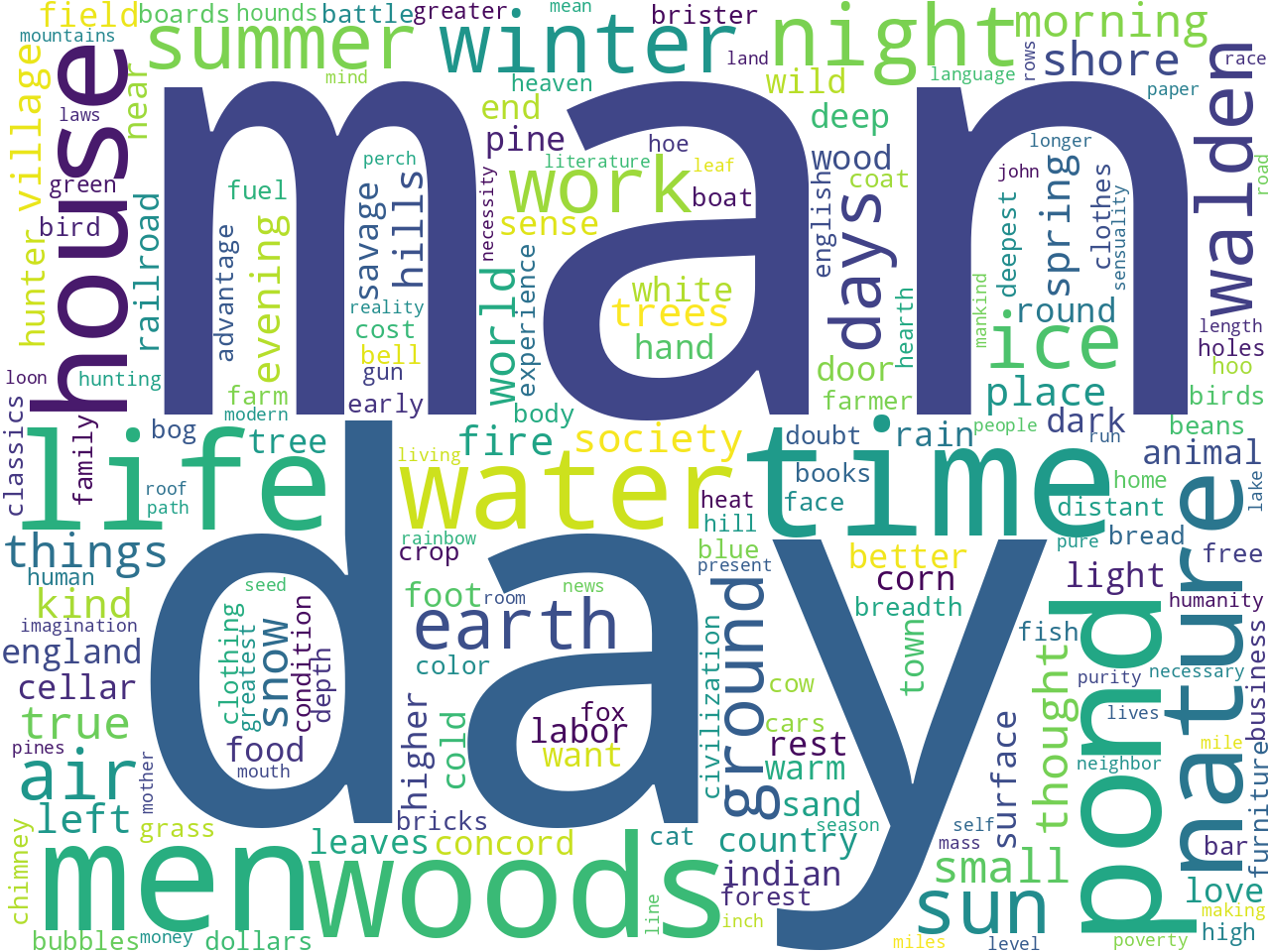

computed keywords

A man (human) in nature

In the early 1800's a man named Henry David Thoreau retreated for about eighteen months to a placed called Walden Pond which is located outside Concord (Massachusetts, United States). There he lived in a little cabin, grew beans, took long walks, and had interactions with his neighbors. The book -- Walden -- first published in 1854, documents the things he felt, thought, and believed during his retreat. Those things have a lot to do with what it means to be a man (human), what it means to be a man (human) in relation to other men (humans), and what it means to be a man (human) in relation to nature.

My analysis -- both above and below -- was done against a copy of Walden found in a set of electronic texts at Infomotions. A local copy can be found in this study carrel. Print it, and read it using the traditional reading process. I'll wait, and you will get a lot out of the process. I promise.

In the meantime, allow me elaborate on some of the more salient characteristics of the book. First of all, Walden is about 108,000 words long. Not very long. [1] It has a Flesch readability score of 71, which means it is pretty easy to read. [2] Peruse a list of the book's chapters and their associated summaries to begin to get a feel for the work.

The following word clouds illustrate the frequency of the most common words (unigrams), most common two-word phrases (bigrams), and most common computed keywords. [3] The word clouds begin to illustrate the aboutness of the book:

unigrams |

bigrams |

computed keywords |

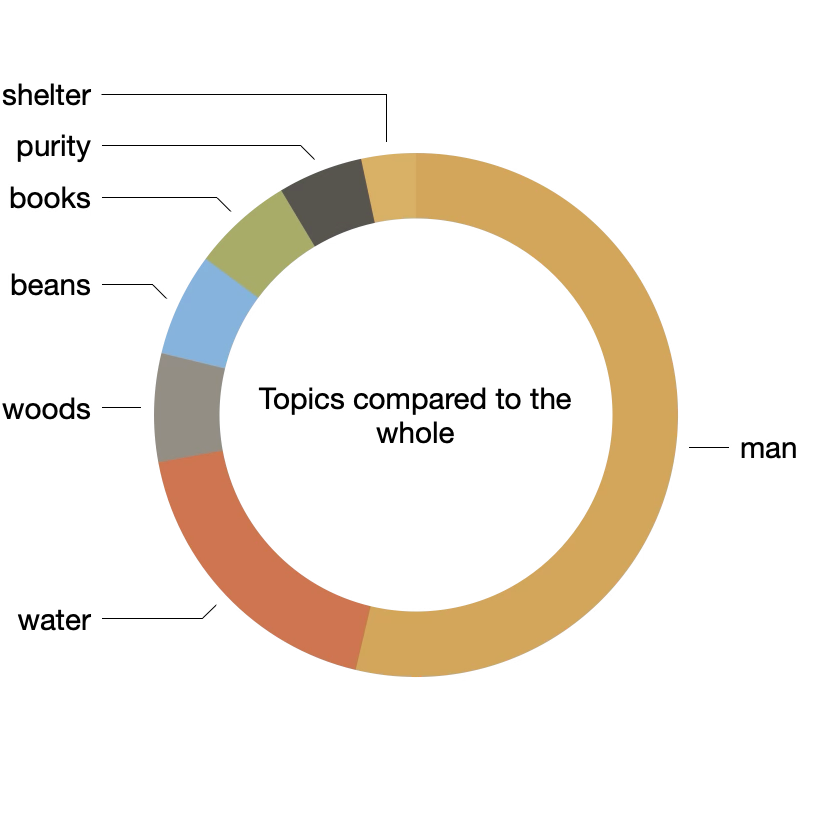

Another way to characterize the book is through the application of "topic modeling". [4] Topic modeling is almost just as much an art as it is a science. That said, I applied topic modeling to the book, and in the end I enumerated the following seven latent themes:

| labels | weights | features |

|---|---|---|

| man | 1.64 | man life men house time day part world get morning work thought |

| water | 0.56165 | water pond ice shore surface walden spring deep bottom snow winter summer |

| woods | 0.2046 | woods round fox pine door bird snow evening winter night suddenly near |

| beans | 0.19471 | beans hoe fields seed cultivated soil john corn field planted labor dwelt |

| books | 0.19032 | books forever words language really things men learned concord intellectual news wit |

| purity | 0.16002 | purity evening body warm laws gun humanity streams sensuality hunters vegetation animal |

| shelter | 0.10274 | shelter clothes furniture cost labor fuel clothing free houses people works boards |

In other words, I assert the dominent theme is "man", where "man" is a label for the hyphenated phrase man-life-men-house-time-day-part-world-get-morning-work-thought. The second-most dominant theme is "water" (water-pond-ice-shore-surface-walden-spring-deep-bottom-snow-winter-summer). And so forth. Notice how these computed themes echo the content of the word clouds. When modeling is done correctly, such things should not be a surprise. In fact, they ought to be expected, if not a source of verification.

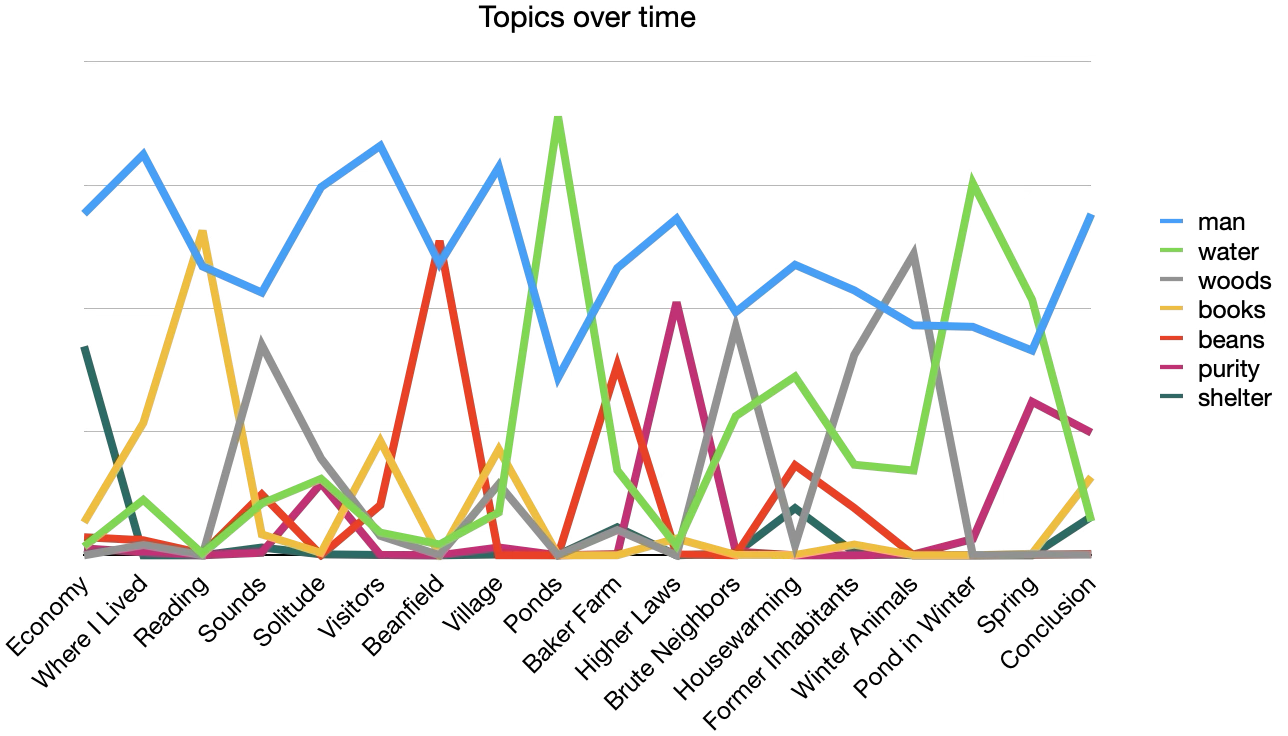

The latent themes can be visualized in at least two ways. The easiest is via a pie chart illustrating the degree each theme is related to the whole. The more interesting visualization -- in my humble opinion -- is the line chart. It illustrates how the themes ebb and flow over the course of the book. From the charts below we see how more than half of the book is about "man", and "man" is a constant theme running across the book's chapters. Additionally, in the line chart, notice the spikes when it comes to "books", "water", and "beans". Notice how these themes correspond to the titles of the chapters. This is not a coincidence. Instead, it is evidence of good writing style.

topics |

topics over time |

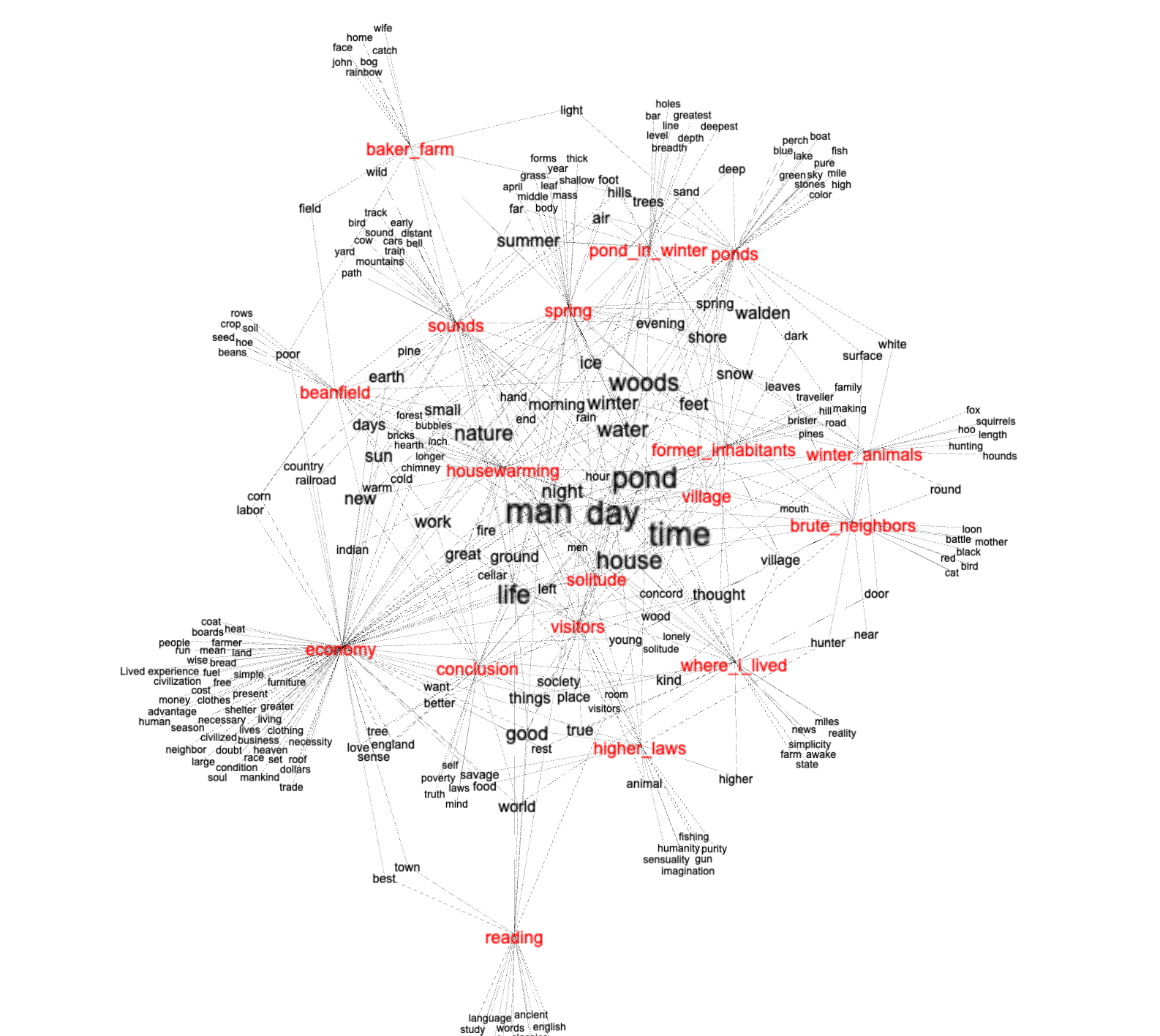

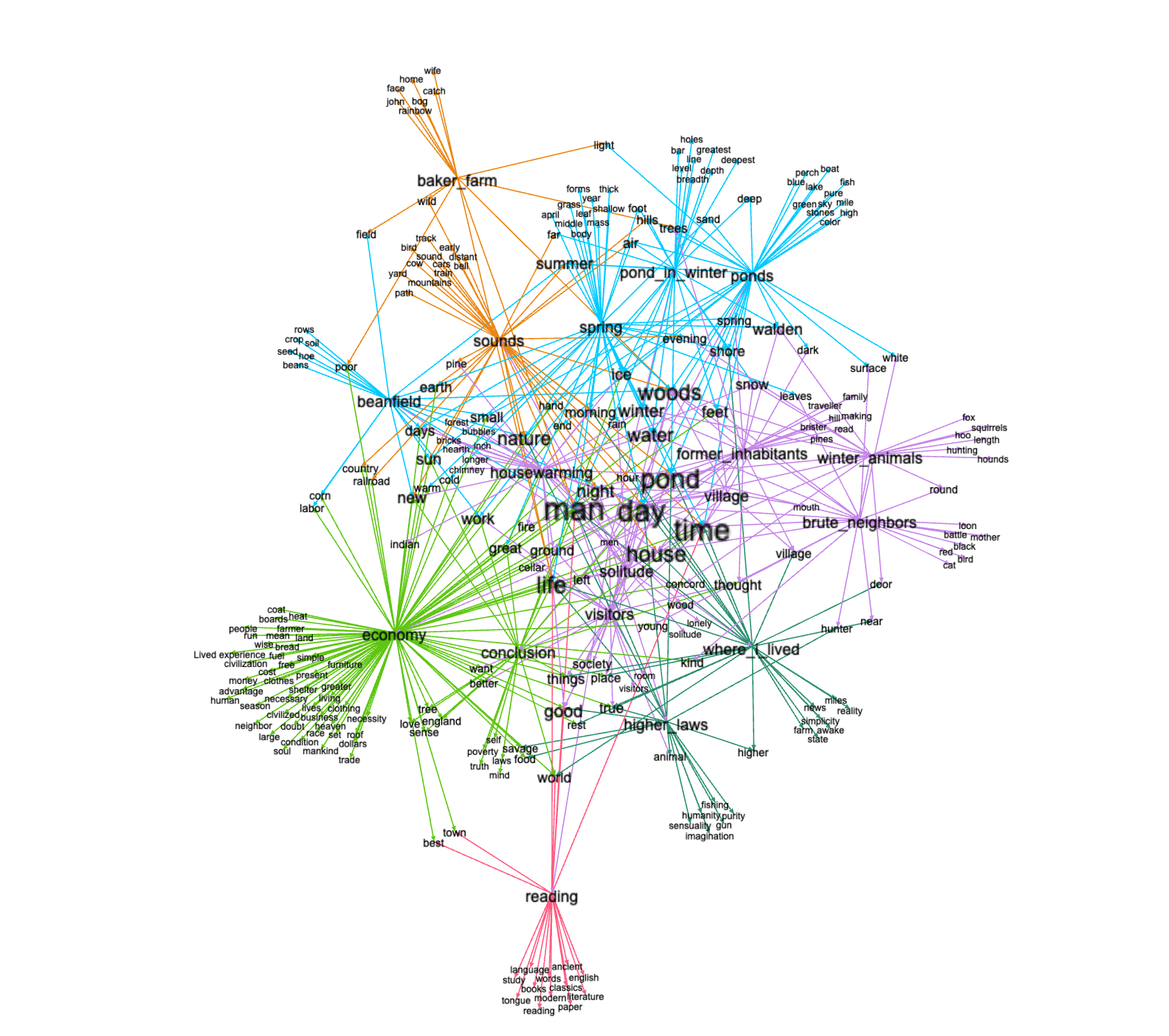

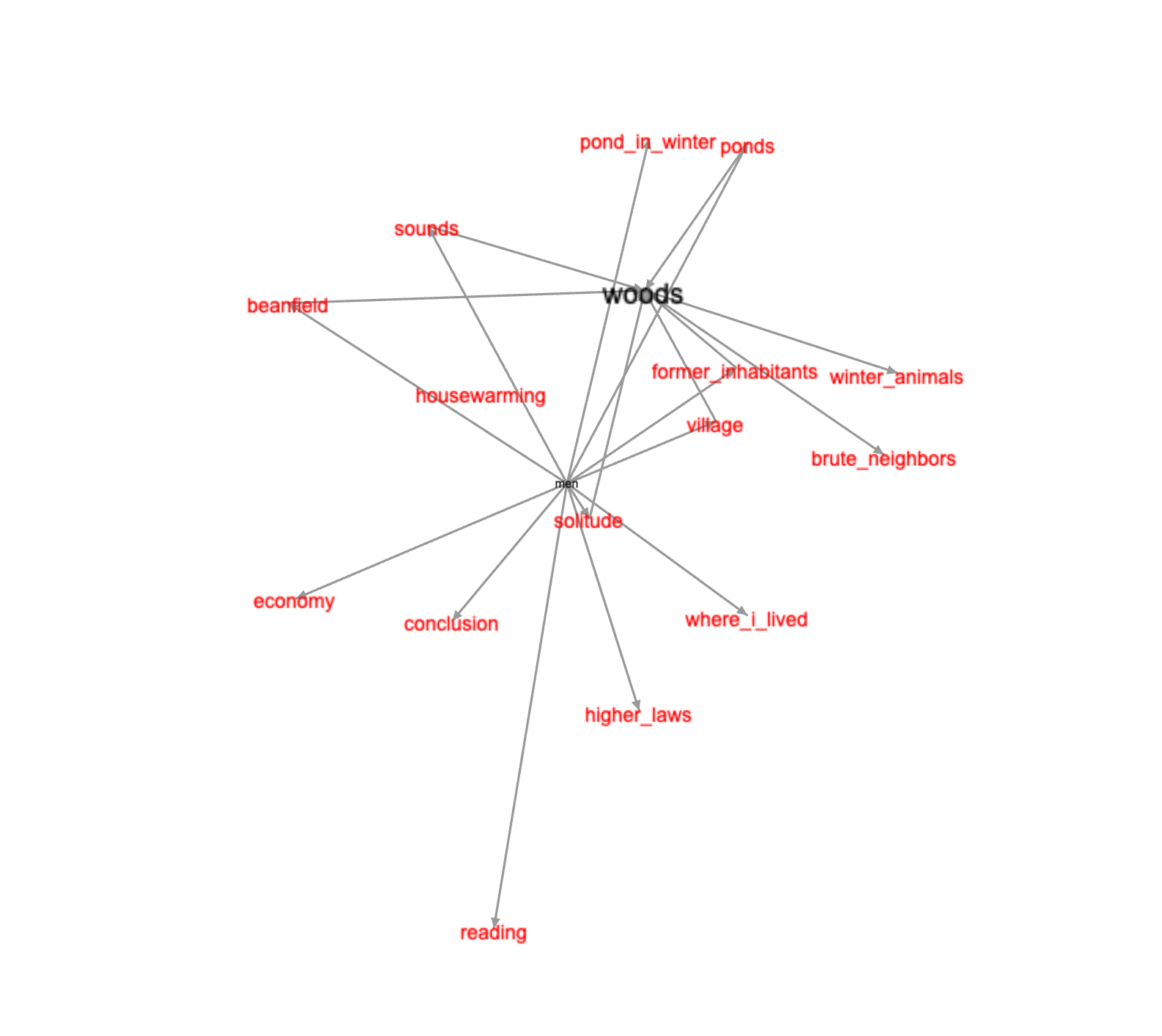

Network graphs are another interesting way to model ("read") a text. [5] In the first network graph -- items and keyword -- each chapter is in red and the chapters' associated keywords are in black. From the illustration you can see that "man", "day", "pond", "time", and "house" are literally central themes; each of these words are shared by many chapters.

The second network graph -- clusters -- is the result of a applying modularity to the networks, and modularity computes neighborhoods of nodes. Given this analaysis, I assert the chapters named "beanfield", "spring", "ponds in winter, and "ponds" all elaborate on similar topics. Notice the chapter named "reading" it is different from all the rest. It, like "economy" is distinct.

When traversing a network there are some nodes which must be gone through more often in order to get to other nodes. Such nodes have a high "betweeness" value, and such nodes can be considered significant. After computing the betweeness values of all the nodes in the network, and them removing the nodes with betweeness values of 0, the last network graph is presented -- betweeness. How to interpret this graph? It tells me, the keywords "man" and "woods" are very significant, and if I want to read about these things, then I need to read the associated chapters. For extra credit, address the following question, "What chapters might I read if I want to read about man and woods?"

items and keywords |

clusters |

betweenesses |

As I have asserted more than a few times, Walden is about "man", but I believe the word should really be "human". Granted, Thoreau only uses the word "woman" or "women" a few times in the book:

arer to town, zilpha, a colored woman , had her little house, where sh this morning, nor a boy, nor a woman , i might almost say, but would un the gauntlet, and every man, woman , and child might get a lick at k which you may call endless; a woman 's dress, at least, is never don roduced to a distinguished deaf woman , but when he was presented, and of luxuries; and i know a good woman who thinks that her son lost hi

sides of a chaise at once, and women and children who were compelled ey who edit and read it are old women over their tea. yet not a few a state which buys and sells men, women , and children, like cattle, at ke up the strain, like mourning women their ancient u-lu-lu. their di ion when we begin to be men and women . it is time that villages were ish and savage taste of men and women for new patterns keeps how many e experiments, though a few old women who are incapacitated for them, ain poor. while my townsmen and women are devoted in so many ways to were not england's best men and women ; only, perhaps, her best philan nd ladies, are not true men and women . this certainly suggests what c rprising how many great men and women a small house will contain. i h itors. girls and boys and young women generally seemed glad to be in

From my perspective, all of the mentions are benign, and none of them are belittling. Yes, Thoreau was writing in a time when women did not have very much respect, and yes things were a lot about men, but from my perspective Thoreau was really writting about what it means to be human but used the word "man". (The concordance for the word "man" is too long for this posting -- more than 300 lines, but I have cached it locally for your perusal.) Similarly, when Thoreau does use the word "human" the usage is what we would expect today:

From my perspective, Thoreau was writing in the style of the times; even though he uses the word "man" liberally, I do not believe he was a chauvinist.f thawing clay? the ball of the human finger is but a drop congealed. of the body. who knows what the human body would expand and flow out mes their winter supply. so our human life but dies down to its root, eir dark line was my guide. for human society i was obliged to conjur nce were the stir and bustle of human life, and "fate, free will, for little does the memory of these human inhabitants enhance the beauty man; almost the only friend of human progress. an old mortality, say s, of fallen souls that once in human shape night-walked the earth an her choir the dying moans of a human beingsome poor weak relic of mo howls like an animal, yet with human sobs, on entering the dark vall ourselves to speculate how the human race may be at last destroyed. but actually breathed from all human lips;not be represented on canv knowledge of the history of the human race; for it is remarkable that ly unknown. the whole ground of human life seems to some to have been at the same moment! nature and human life are as various as our seve use has become, so important to human life that few, if any, whether n impartial or wise observer of human life but from the vantage groun ime when, in the infancy of the human race, some enterprising mortal ; where i see in my daily walks human beings living in sties, and all e greatest genuine leap, due to human muscles alone, on record, is th e country is not yet adapted to human culture, and we are still force ied the same and succeeded. the human race is interested in these exp es from goodness tainted. it is human , it is divine, carrion. if i kn small boy, perhaps without any human being getting a glimpse of him. ny noise that i could hear, and human soldiers never fought so resolu the ferocity and carnage, of a human battle before my door. kirby an a true humanity, or account of human experience. they mistake who as is a part of the destiny of the human race, in its gradual improvemen y of the necessary functions of human nature. in earlier ages, in som posed to contain an abstract of human knowledge, as indeed it does to night was never profaned by any human neighborhood. i believe that me made the fancied advantages of human neighborhood insignificant, and h more. i only know myself as a human entity; the scene, so to speak, aders who has yet lived a whole human life. these may be but the spri ligence that stands over me the human insect. there is an incessant i etimes, having had a surfeit of human society and gossip, and worn ou wild ducks come. nature has no human inhabitant who appreciates her.

[1] By way of comparision, the Bible is about 800,000 words long, and Melville's Moby Dick is about 218,000 word long. Based on my experience, the typical scholarly journal article is between 5-8,000 words long. For extra credit, address the following question, "How long is Walden measured in journal articles?"

[2] A Flesch readability score is a number between 0 and 100, where 0 means nobody can read the item, and 100 means everybody can read the item. The score is rooted in the number of words, the sizes of words, the number of sentences, the sizes of sentences, and the size of the underlying vocabulary. For more detail, see the Wikipedia page.

[3] Sets of keywords can be computed by comparing the relative frequency of a given word in a text compared to the number of times the given word appears in the corpus as a whole. Such is a well-respected algorithm called Term Frequency / Inverse Document Frequency (TFIDF). See Wikipedia for more detail.

[4] In a sentence, "Topic modeling is an unsupervised machine learning process used to enumerate the latent themes in a corpus." In layman's terms, it is form of clustering. For more detail, see the corresponding Wikipedia page.

[5] Network graphs are abstractions consisting of nodes ("things") and relationships connecting those nodes, which are called "edges". When it comes to a book, there may be chapters (nodes). The aboutness of each chapter may be represented with one or more keywords (more nodes). Lines (edges) can be drawn connecting chapters to keywords to form graphs. Given enough nodes and enough edges, some very interesting patterns emerge which end up telling storires -- characterizing -- the graphs, which is really a representation of the book. For more detail regarding network graphs, begin with Wikipedia.

This "reading" of Walen was done against a data set called a Distant Reader "study carrrel". Given a set of narrative texts -- such as journal articles or etexts -- a thing called the Distant Reader Toolbox applies various natural language processing techniques to the texts and saves the results in file formats readable by people as well as computers. The files can be computed against ("analyzed") and reports can be generated.

Such is what I did with Walden. To learn more, see the readme file that comes with every study carrel, browse the content of the carrel, and read the carrel's automatically generated summary page. By doing so, you will learn a whole lot more about the book. I promise.

Study carrels is intended to be platform- and network-independent, thus they are intended to stand a test of time. That said, download the carrel from here, and consider doing your own "reading":

http://carrels.distantreader.org/curated-walden_by_thoreau-gutenberg/index.zip

Eric Lease Morgan <eric_morgan@infomotions.com>

Lancaster, Pennsylvania (United States)

September 24, 2025