how does internet usage influence the social capital, connectedness, success, and well-being of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka?

1. introduction

the internet has changed the nature and transference of information and communication. now called the world's largest knowledge depository and most efficient communication channel, the internet can increase technology transfer to developing countries, leading to their success in technological and economical development (undp, 2001). apart from the technological and economic influences of information and communication technologies (ict), an argument is emerging regarding their influence on social and psychological aspects of life. icts, led by the internet, will bring significant technical, economic, and social changes to different types of communities in different parts of the world (thakur, 2009). not all of these changes will be positive. according to the recent studies, internet usage has influenced knowledge development, social thinking, and subjective well-being (kraut et al 2002; contarello & sarrica, 2007; weiser, 2004). the internet has redefined the way social relationships are progressing (kraut et al 2002). a recently concluded world values survey found a positive relationship between internet usage and happiness (kelly, 2010). the many influences of internet usage, in other words, will go beyond objective definitions of success in life, and may also influence social and psychological aspects of individual and community life (pigg & crank, 2004).

2. context of the study

a research report by the national endowment for science, technology and the arts (nesta) on the new realities of innovation indicates that the internet is rapidly creating product users as grassroots-level inventors (nesta, 2008). in addition, the internet has been identified as a critical success factor for modern innovative businesses (sparks & thomas, 2001). further, internet usage is considered one of the major contributors to improvements in r&d activities and innovation (kafouros, 2006). as the number of inventions has grown with the expansion of the internet, there is also evidence that internet usage has influenced inventors (wipo, 2007). a survey of the state of georgia's independent inventors also indicated that the internet is among the top three resources of commercially successful inventors (georgia tech enterprise innovation institute, 2008). according to the previous literature, independent inventors are the major source of technological innovations in most developing countries (gupta, et al., 2003). the majority of the patent applications in developing countries have been put forward by ordinary individuals of those countries (weick & eakin, 2005). however, owing to the drastic growth of the organizational and cooperate innovations, attention given to the individual, independent, or garage inventors has been very modest. hence, there has been no formal definition to recognize independent-level inventors (wettansinha, wongtschowski & waters-bayers, 2008).

in eastern literature, the lowest layers of a system are often called the grassroots level. owing to the drastic growth of cooperatives, and institutional and university inventors, ordinary people engaged in inventive activities have become the lowest layer of the innovation system. hence, the present study defines grassroots-level inventors as local individuals of a country, involved in patentable inventive activities and trying to obtain patents for themselves, for their own reasons and own rewards, outside the formal organizational structures of firms, universities and research labs (wickramasinghe c. n., ahmad, rashid & emby, 2010).

3. research problem and aim of the study

owing to the independent nature of the grassroots-level inventive activities, they do not receive the resources, knowledge, and social attention required by employed inventors in multinational companies or research institutions. hence, the objective and subjective achievements and social connectedness of grassroots-level inventors heavily depend on the information, knowledge, and resources they gain from available sources. the internet has proven its ability to provide most of the resources, or at least easier ways to access the required resources for poor and underprivileged communities of the society (sarrica, 2010). hence, the internet has been a significant driving force in the continuation of the grassroots-level inventive community in modern knowledge society. even though the influences of internet usage on objective achievements have studied extensively, the influence of internet usage on social and subjective achievements of the communities has not been studied to such an extent. comprehensive efforts to explain the empirical evidence of the objective, subjective, and social impact of internet usage on grassroots-level inventive communities in lower and middle income countries are especially rare.

sri lanka is a multi-ethnic, lower middle-income island nation in south asia with a population of 20 million in 2009. relative to other south asian countries, sri lanka has a comparatively high income level and human development index, but the country has fallen behind the technological development compared to countries in neighboring south-east asia (wickramasinghe & ahmad, 2009). in sri lanka, 85% of the annual patent applications are forwarded by grassroots-level independent inventors. this percentage has grown throughout the last decade. (wickramasinghe c. n., ahmad, rashid & emby, 2010). however, most of the objective success measures for grassroots-level inventors, such as the number of patents, patent citations, commercialized inventions, and profits, have not been very promising (wickramasinghe c. n., ahmad, rashid, & emby, 2011). these inverse objective outcomes have raised questions about why these grassroots-level inventors continue to engage in inventive activities, and how internet usage has influenced their inventive lives. therefore, this paper aims to explore the influence of internet usage on the social capital, community connectedness, and objective and subjective well-being of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka.

4. theoretical model

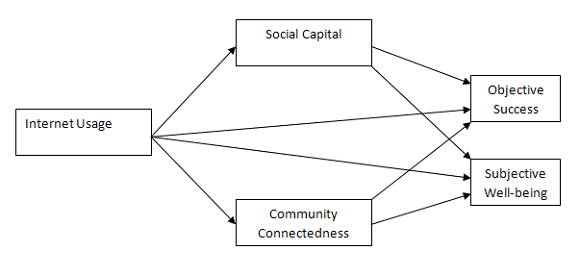

recent literature on internet usage has focused on the influence of internet usage on the social capital, community participation, and empowerment of different social segments of the society (haythornthwaite & kendall, 2010; robinson & martin, 2010; pénard & poussing, 2010). a number of studies explain the influence of internet usage through social networking and the subjective well-being of social groups (bruke, marlow & lento, 2010; sum, mathews, pourghasem & hughes, 2009). however, none of the studies attempts to explore how internet usage might influence the social capital, connectedness, and objective and subjective success of grassroots-level inventors. based on the theoretical and empirical evidence of the previous literature, the researchers developed a correlational research model to explore how internet usage influences the social capital, community connectedness, objective success, and ultimately the subjective well-being of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka (figure 1).

5. method

5.1. conceptualization and operationalization

5.1.1. internet usage

even though the internet can be used for various general and casual purposes, in the present study internet usage is operationally defined as the grassroots-level inventors' use of the internet for knowledge and information collection, sharing, and communication. rodgers and sheldon (2002) developed the web motivation inventory (wmi) scale centered on four factors: researching, communicating, surfing, shopping. they used a 5-point likert scale including three items for each factor (rodgers, jin, rettie, alpert, & yoon, 2005). in the present study, researchers measured the grassroots-level inventors' usage of the internet only for their information, knowledge, and communication needs. therefore, items that measure the shopping motive were considered irrelevant. researchers modified the wmi scale items to develop a shorter scale, while keeping the five likert points: 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4= agree, and 5= strongly agree (& alpha; = .868).

5.1.2. social capital

phillips and pittman (2009) defined social capital or capacity as the extent to which members of a community can work together effectively to develop and sustain strong relationships to solve problems, make group decisions, and collaborate effectively to plan, set goals, and get things done (phillips & pittman, 2009). social capital improves subjective well-being by giving opportunities for the community members to share knowledge, resources, and feelings (winkelmann r., 2009). hence, social capital is one of the primary features of socially organized communities, allowing citizens to resolve collective problems (wiesinger, 2007). as grassroots-level inventors are involved in inventive activities as individuals, measuring their individual social capital is considered meaningful. therefore, the present study approached social capital from the individual perspective to identify how grassroots-level inventors received required resources from their social relationships. past studies confirmed that individual-level relationships with family, friends, neighbors, and other social organizations positively contributed to subjective well-being (helliwell & putnam, 2004; hooghe & vanhoutte, 2009). the present study measured individual social capital using gaag's (2005) 17-item resource generator scale, integrated with the response structure of granovetter's (1973) strong, weak, and absent social ties. in present study, 17 items of gaag's individual social capital resource generator scale were translated to sinhala language by changing only the currency of item number 4 to sri lankan rupees. the researchers also modified the response options of the resources generator scale as follows: 1=no, 2=official level, 3=friend's friend, 4=friend, 5=relative, and 6=family member. higher summated scores represent strong social capital, and lower summated scores represent weak social capital (& alpha;=.737).

5.1.3. community connectedness (sense of community)

community connectedness, or sense of community, is a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members' needs will be met through their commitment to be together (mcmillan & chavis, 1986). past studies have found social connectedness and sense of community positively correlate with subjective well-being (helliwell j. f., 2003; helliwell & putnam, 2004; winkelmann r., 2009; helliwell j. f., 2007). on the other hand, lack of social contacts strongly negatively correlates with subjective well-being (dolan, peasgood, & white, 2008). davidson and cotter (1991) found that a strong sense of community positively correlated with the happiness of the people (davidson & cotter, 1991). instruments exist to measure the sense of community (community connectedness), but they are very long (doolittle & macdonald, 1978; davidson & cotter, 1986). however, frost and meyer (2009) measure the community connectedness of the lesbian, gay and bisexual (lgb) community using a relatively shorter scale. because the lgb community is a community of interest rather than a neighborhood community, this scale was adapted to measure the connectedness of the grassroots-level inventive community. frost and meyer's community connectedness consists of 8 items adapted from a 7-item community cohesion scale used in the urban men's health study (umhs). they added one item, "you feel a bond with other [men who are gay or bisexual," taken from herek and glunt's (1995) community-consciousness scale. their study has shown high validity and cronbach alpha internal consistent value (frost & meyer, 2009). in the present study frost and meyer's community-connectedness scale was modified by replacing the specific words related to lgb community with words related to the grassroots-level inventive community. even though the original frost and meyer's scale has only 4 likert like responses (1=strongly disagree to 4=strongly agree), the present study used more options to describe the nature of connectedness of grassroots-level inventors. it suggested a 7-point likert like scale (& alpha;= .822).

5.1.4. objective success

according to the theoretical argument of the present study, all material and objective outcomes mediate the people's subjective well-being. hence, the tangible and explicit outcomes of the innovation process are not the ultimate success that inventors could achieve. objective success was defined as a mediator variable of the subjective well-being. the present study adopted the hauschildt's innovation process approach to evaluate the objective success of the inventors (hauschildt, 1991). hauschildt explained the importance of measuring the success of innovation at different stages of innovation process. according to him, not every invention goes through all different stages of the innovation process. therefore, measuring the success of inventors only by patent or commercialization measurements is not showing the reality of success. adhering to hauschildt's framework, the present study adapted five different objective measurements to measure inventors' success at each stage of the innovation process: 1) idea generation stage-receiving a patent, 2) competitive evaluation stage-winning an award, 3) market entrance stage-commercialization, 4) market survival stage-surviving in the market, and 5) income earning stage-earning a profit. the researchers initially developed the objective success measurement and asked for advice and comment from a selected panel of experts. when the researchers consulted the work of weick, she advised the use of a limited number of items with dichotomous responses because that is straightforward to measure and avoids complex comparisons (weick c., personal communication, 12th august 2008). weick and eakin (2005) also measured the commercial success of inventors using a multi-item dichotomous (0, 1) scale. therefore, objective success is calculated as the summation of five items measured using a dichotomous scale (0, 1); the patent grants, award and rewards, commercial startup, commercial continuation, and profitable inventions. in the questionnaire researchers asked respondents to state how many patent they received, how many awards and rewards they won, how many inventions started to commercialize, how many were still commercialized, and how many of the inventions earned profits. respondents who reported values higher than one were considered as one, and others considered as zero. by calculating the summation of dichotomous responses, researchers generated the continuous objective success variable ranging from zero to five. that is higher than the four scale values, the minimum recommended range of scales in structural equation and path modeling (hair, black, babin, & anderson, 2009).

5.1.5. subjective well-being

according to the literature, definitions of subjective well-being consist of emotional aspects, which are mostly measured by happiness, and cognitive aspects, which are mostly measured by satisfaction with life. subjective happiness scale (shs) and satisfaction with life scale (swls) are the most administered scales to measure subjective well-being (snyder & lopez, 2007; diener e., 2009). the satisfaction with life scale has been tested for its reliability and validity by the authors, and the test has shown a high level of consistency, validity, and reliability to measure the life satisfaction of different type of domains (diener, emmons, larsen, & graiffin, 1985; pavot & diener, 1993). the subjective happiness scale is a validated instrument that has been widely used, notably in 14 different studies with 2,732 participants (university of pennsylvania, 2007). results have signified that the subjective happiness scale has high internal consistency, and is stable across different types of samples. in order to measure both emotional and cognitive aspects of subjective well-being, integrating the subjective happiness scale and satisfaction with life scale has been practiced by the pichler (2006), rogatko (2010), and (lyubomirsky s., 2008) and therefore, lyubomirsky recommended the researchers to use the integrated scale in the present study (lyubomirsky s., personal communication, 21st february 2010). therefore, in the present study, subjective well-being was measured using a summation of original subjective happiness scale 4 items (lyubomirsky & lepper, 1997) and satisfaction with life scale 5 items (diener, emmons, larsen, & graiffin, 1985). both the scales have seven point likert like responses from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) (& alpha;= .776).

5.2. population and sample

even though not all inventors apply for patents, patent databases are recognized as the only available central depositories of the innovation skills of a nation (jaffe, trajtenberg, & romer, 2002; koch, 1991). hence, the researchers searched the sri lanka national intellectual property office (slnipo) patent database for grassroots-level inventors who applied for patents during the years 2000-2009. researchers identified 640 independent inventors as the target population of the study. then the researchers selected 200 inventors using the stratified random sampling technique based on their living districts. this sample represented 31 percent of the target population. researchers were planning to evaluate conceptual models using model fit indexes of the structural equation modeling. according to the literature 200 is the minimum sample size when the model has more parameters to estimate (kline, 2010). hence, the selected sample size was able to generate results with an acceptable level of power.

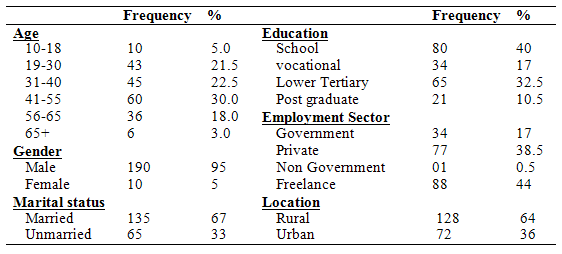

5.3. participants

table 1 depicts the demographic profile of the respondents in the sample. the majority of respondents are middle-aged males. two-thirds of the respondents are married, and 60 percent of the respondents had completed either a vocational or university level education. the majority of the respondents are self-employed, with freedom of choice about what they are doing. two-thirds of the respondents live in rural areas of sri lanka; according to the existing rural-urban classification in sri lanka, 80 percent of the population is rural.

demographic factors of the respondents in the sample, such as age, gender, marital status, education, and employment status are similar to studies on independent inventors in developed countries. the majority of those studies found that the common independent inventor is a middle-aged married male with a high level of education and is involved in self-employed economic activities (sirilli, 1987; amesse & desranleau, 1991; weick & eakin, 2005; georgia tech enterprise innovation institute, 2008). however, previous studies have identified that a majority of independent inventors are living in metropolitan rather than rural areas. at present the urban and rural classification in sri lanka has been done based on the size of the lowest political administrative divisions of the country. in most developed countries the classification is based on the density of the population (united nations, 2007). apart from the differences owing to these classifications, in general sri lankan grassroots-level inventors show a demographic profile similar to independent inventors in developed countries. hence, the sample of the present study is a representative cross-section of the universal independent inventors' community.

5.4. procedure

the required data was collected using a self-administered questionnaire known as the sri lanka independent inventors survey (slis 2010), which was carried out by the researchers from the months of february to august 2010. researchers invited the randomly selected respondents to participate in data collection panels organized at centers located in four metropolitan districts in sri lanka. after explaining the aims and objectives, researchers explained the structure of the questionnaire and specific instructions to answer it properly. after clarifications, respondents were asked to answer the questionnaire and by quickly scanning for missing values, researchers ensured that respondents answered all the questions in the questionnaire. after collecting the data, researchers entered the data into the spss software package and conducted the exploratory data analysis (eda). during the eda, researchers tested the assumptions of outliers, normality, linearity, and multicolinearity. owing to the fact that researchers were planning to adapt the path analysis statistical method for model development and comparison, researchers tested the multivariate normality and multivariate outlier of the variables in the model using critical values of the mardia kurtosis.

6. results

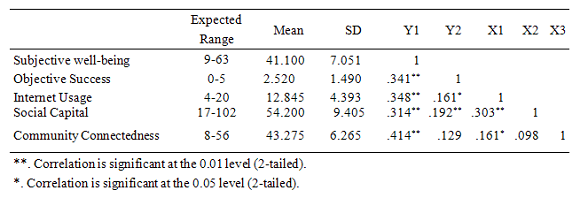

table 2 presents the correlation between the variables in the present study. further, it depicts the maximum expected ranges, means, and standard deviations of the variables.

according to table 2, the respondent grassroots-level inventors have a high moderate level of subjective well-being (m=41.1, sd=7.051). then again, they have achieved only moderate-level objective success (m=2.52, sd=1.490). even though the respondents have shown a high level of community connectedness (m=43.275, sd=6.265), they have achieved only moderate-level social capital (m=54.200, sd=9.405). respondent inventors are also moderate-level internet users (m=12.845, sd=4.393).

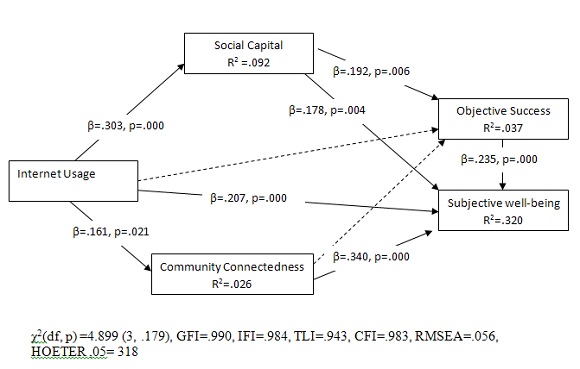

according the pearson product movement correlation coefficients (r), all the exogenous variables of subjective well-being show moderate level correlation at .01 level. however, the relationships between objective success and internet usage (r=.161, p<.05), and objective success and social capital (r=.192, p<.01), show only low level correlation. further, the relationship between objective success and community connectedness (r=.129, p>.05) is not statistically significant at .05 level. hence, the results indicate that inventors' community connectedness has no influence on their objective achievements of their inventive activities. according to the correlation analysis, there was no threat of multicolinearity between exogenous variables of the hypothetical model. hence, the researchers continued data analysis with path analysis using spss amos software version 19. after two iterations of modifications by removing insignificant paths of the model, the researchers were able to develop the optimal model of the study (figure 2).

all the indices presented in figure 2 satisfy the generally accepted cut-off levels recommended by kline (2010). hence, the modified model presented in figure 2 can be considered the statistically significant final model of the present study. all the exogenous and mediator variables of the model were able to explain 32% of the variance of the ultimate dependent variable, subjective well-being (r2=.320). hence, internet usage, social capital, community connectedness, and objective success are able to explain 32% of the variance of the happiness and satisfaction of grassroots level inventors in sri lanka.

according to figure 2, internet usage has a significant positive direct influence on the social capital (& beta;=.303, p=.000), community connectedness (& beta;=.161, p=.021), and subjective well-being (& beta;=.207, p=.000) of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka. even though the expectations were high for the influence of internet on the technological development of developing countries, results indicate that there is no significant direct influence of internet usage on the objective success of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka. however, through social capital, internet usage indirectly influences objective success. bias-corrected percentile bootstrapping of 2000 samples indicates that the indirect influence was statistically significant (& beta;=.058, two tailed sig.=.001). hence, internet usage has significant indirect influence on the objective achievements of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka through influence of social capital. however the strength of the influence is not very strong.

unlike with objective success, internet usage has a significant direct influence on the subjective well-being of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka (& beta;=.207, p=.000). further, through social capital and community connectedness, internet usage has indirect influence on subjective well-being. according to the bootstrapping results, the indirect influence of internet usage on subjective well-being through social capital and community connectedness is statistically significant (& beta;=.122, p=.001). statistical results of the present study indicate that internet usage is a significant predictor of social, community, and subjective well-being of grassroots-level inventors. however, internet usage is not a significant strong predictor of inventive achievements and success of grassroots level inventors in sri lanka.

7. discussion and conclusion

even though there has been hype about the impact of the internet on the technological achievements of developing countries, findings of the present study do not support that argument. according to the path analysis results, internet usage has not significantly influenced the objective success of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka. the findings suggest that even though there is moderate-level internet usage among grassroots-level inventors, still there is a significant gap between inventors' internet usage as information and communication medium to gain knowledge. the comments made by the respondents at the discussions also suggested that the majority of them have no internet connections at their homes and they are not aware how to search for patent and innovation information on the internet (wickramasinghe, 2010). the results indicate the impact of the internet on inventive success has been exaggerated in developing countries like sri lanka. therefore, the lack of internet access and a knowledge divide about the usage of digital content in sri lanka might explain the low impact of internet usage on the objective success of grassroots-level inventors.

community connectedness also shows no significant influence on objective success. unlike in industrial countries, there is no platform for collaboration among the grassrootslevel inventors in sri lanka. findings related to community connectedness indicate the physically scattered and individualistic nature of the grassroots-level inventor community in sri lanka. even though they are emotionally attached to each other, in a practical sense there was no attachment among inventors to support each other. therefore, emotional attachment was unable to provide fruitful contributions to the inventive activities through knowledge and resource sharing among the members of the community. according to the comments made by the grassroots-level inventors at the panel discussions, there is a desperate need for forming a common platform that would allow the convergence of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka to build stronger ties. hence, technological policy developers have to consider this as a prioritized need to be satisfied sooner rather than later.

social capital has been the only significant influential factor of the objective success of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka. it suggests that grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka are receiving required resources from their individual social relationships rather than within the inventive community. hence by providing opportunities for inventors to interact with social structures and groups that can contribute to their inventive activities, sri lanka might be able to increase the success of its technological inventions in the future.

even though internet usage and community connectedness do not significantly influence objective success, both these variables significantly contribute to the subjective well-being of grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka. findings suggest the significant value of internet usage on developing social capital, community connectedness, and ultimately subjective well-being among the inventive community of sri lanka. although grassroots-level inventors have not achieved a high level of objective success from their inventive activities, whatever they have achieved from their inventions positively influences their general happiness and satisfaction with life. hence, inventive activities have been a significant life domain of grassroots-level inventors of sri lanka, contributing to their subjective well-being. this might be the reason that they are continuing in inventive activities, even as they do not achieve higher objective success.

the internet has been identified as a tool that allows technological knowledge transfer from developed to developing countries. hence, most developing countries have given serious attention to developing internet-based information and communication technologies to bridge the digital divide without concerning "for what." however, the present study found that internet usage among grassroots-level inventors in sri lanka is at a moderate level, and that internet usage does not significantly influence the objective success of the inventors. hence, current internet usage might not influence innovation development in sri lanka. therefore, technological knowledge transfer has not happened in sri lanka as expected. however, findings of the study suggest that internet usage has been a significant predictor of happiness and life satisfaction among the inventors. therefore, the internet has been a significant contributor to the subjective quality of life of the inventors. that suggests that inventors use the internet as a social communication medium rather than a technological knowledge source. findings of the study suggest that not only are improvements needed in sri lanka's infrastructure development and internet access, but also that inventors must improve their own technical awareness and language skills before gaining the potential of the internet as a technological knowledge source.

the study found that subjective happiness and satisfaction largely depend on inventors' self-evaluation of existing outcomes and expectations for the future. therefore, inventor assessment programs in developing countries should not overemphasize assessing inventors based on pure objective measures such as number of patents, patent citations, awards and rewards, commercialized inventions, or profitability. overemphasis on these factors might create pessimistic thinking and uncertainty among the inventors about their inventive lives, and could create extra burden on the inventors, perhaps even leading some to give up inventive activities or find easier ways to achieve subjective success in life than being an inventor. therefore, independent inventors in developing countries should be considered national assets, and should be evaluated in a more constructive way than with a potentially destructive straightforward "successful" or "unsuccessful" binary type of evaluation.